Good professional development just doesn’t happen on its own. Along with timely execution by a knowledgeable instructor that respects adult learning, to meet the ISTE coaching standard 4, professional development also needs support by administrators. While it is clear to me that administrators inform policies and procedures that govern culture in an institution, I must admit that I do not have a lot of background knowledge nor intimate understanding of the process administrators use to determine professional development. For this post, I’d like to investigate that process a little more closely. In particular, I would like to take a closer look in to understanding what role administrators play in the successful implementation of professional development.

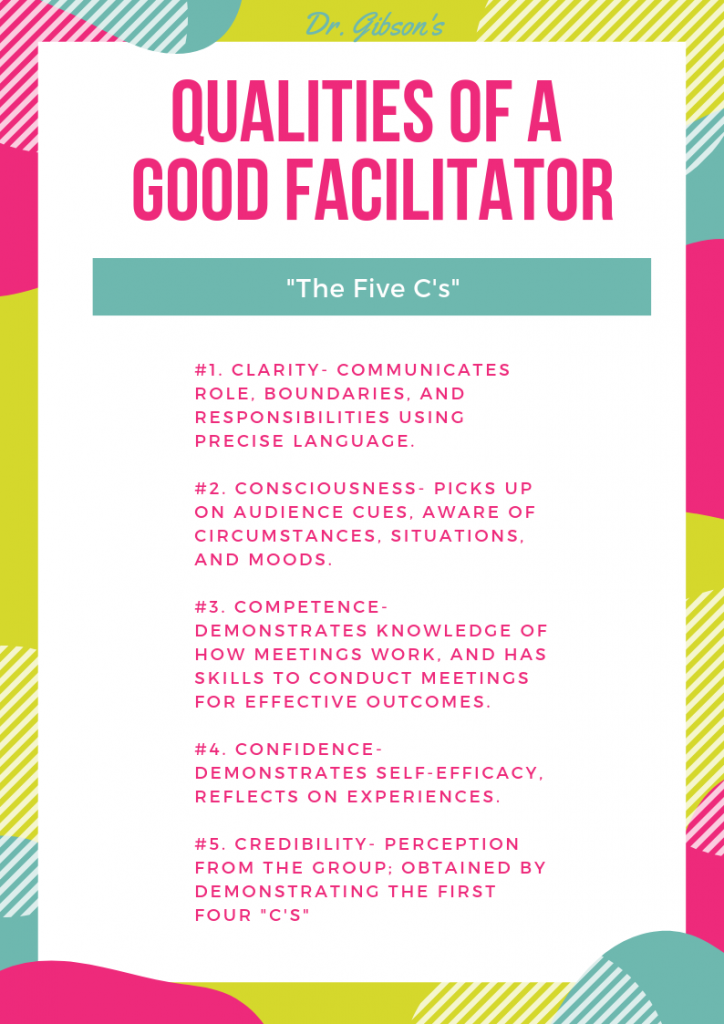

Through my investigation, I gathered insight into what administrators face on a daily basis. Much like the changing landscape for teachers in implementing strategies and methods needed for 21st century skills, administrators are faced with the same predicament in engaging students and teachers with these skills. What is unique to the administrator’s challenge is that they have the added responsibility of initiation. Change starts with them so their attitudes and behaviors mirror the rate of success in improvement. Administrators who value technology and the development of 21st century skills are then viewed as technology leaders who must demonstrate willingness to learn, be flexible, and accept on-going change for technology adoption and implementation to occur, (Grady, 2011). An administrator’s role as a technology leader begins by setting a clear vision and understanding the standards that govern that vision, (Grady, 2011). Grady’s view on the administrator’s qualities mirrors that of the ISTE standard in the fact that not only are vision and goals to be communicated to faculty but good administrators model good technology use in various modes, provide engaging professional development, and engage in continuous professional development themselves as a lifelong learner, (Grady, 2011). Grady also shares that administrators that are good technology leaders also recognize faculty at the cornerstone of implementation, (Grady, 2011). Therefore, while professional development may create awareness about specific policies, it is understood true implementation requires more action and evaluation.

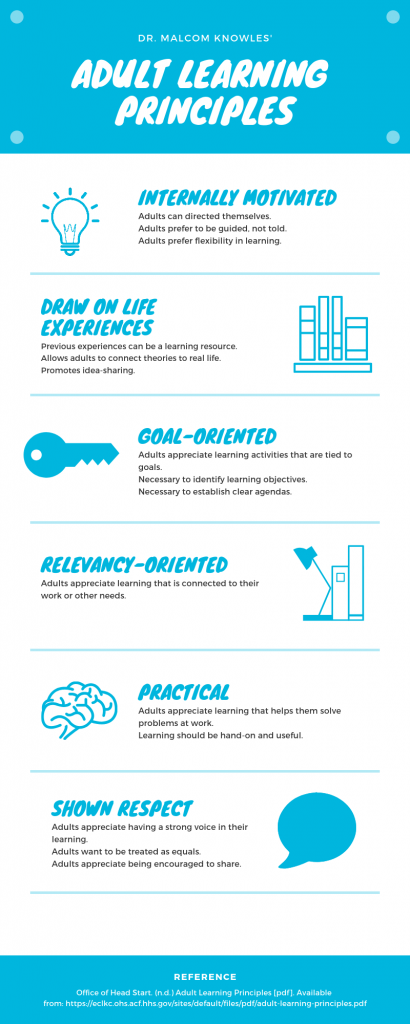

Former teacher turned administrator, Lyn Hilt, shares her investigation and thoughts on the administrator’s role in implementing successful professional development. After reflecting upon her experiences undergoing professional development as a teacher and having no recollection of anything that she implemented from those experiences, she concludes that rather than engaging in “development”, institutions should adopt the idea of “professional learning.” One key facet that Hilt wishes the reader to consider is that “teachers are not vehicles through which schools deliver programs and policies,” (Hilt, 2011). Instead Hilt offers the idea that teachers are individuals with passions and interests, so an administrator’s true role is to foster a desire to learn, (Hilt, 2011). Hilt buys in to the notion that teachers are adult learners and therefore effective “development” should take this into consideration. When teachers elicit true excitement about learning, that learning becomes implemented into their teaching, (Hilt, 2011).

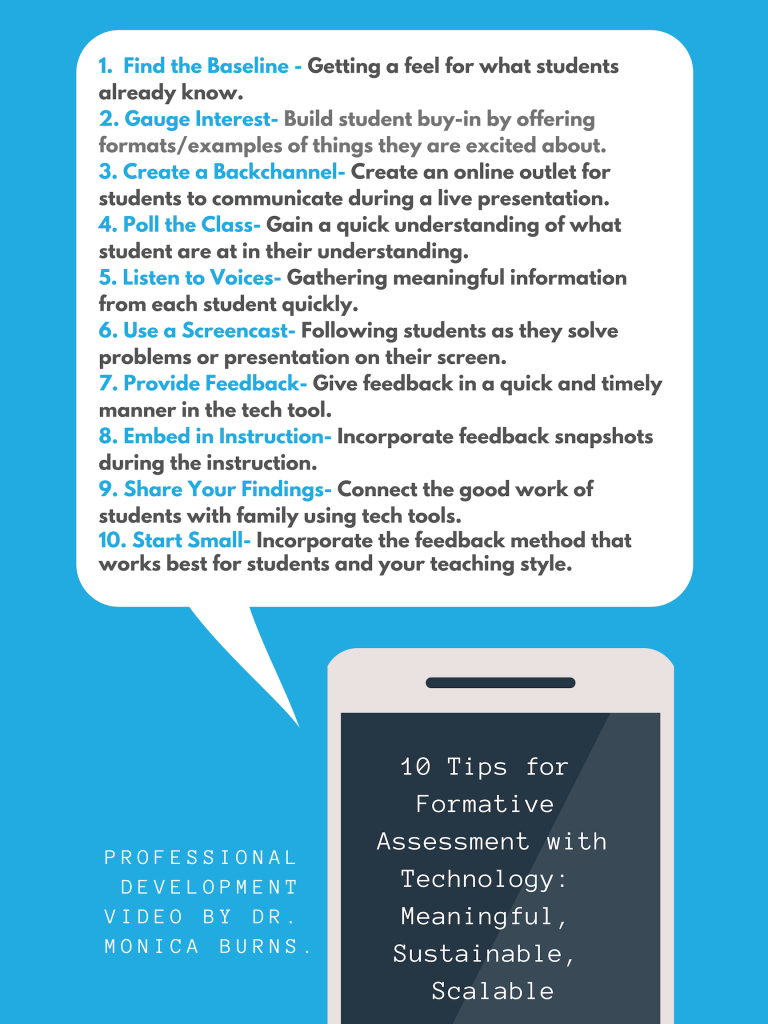

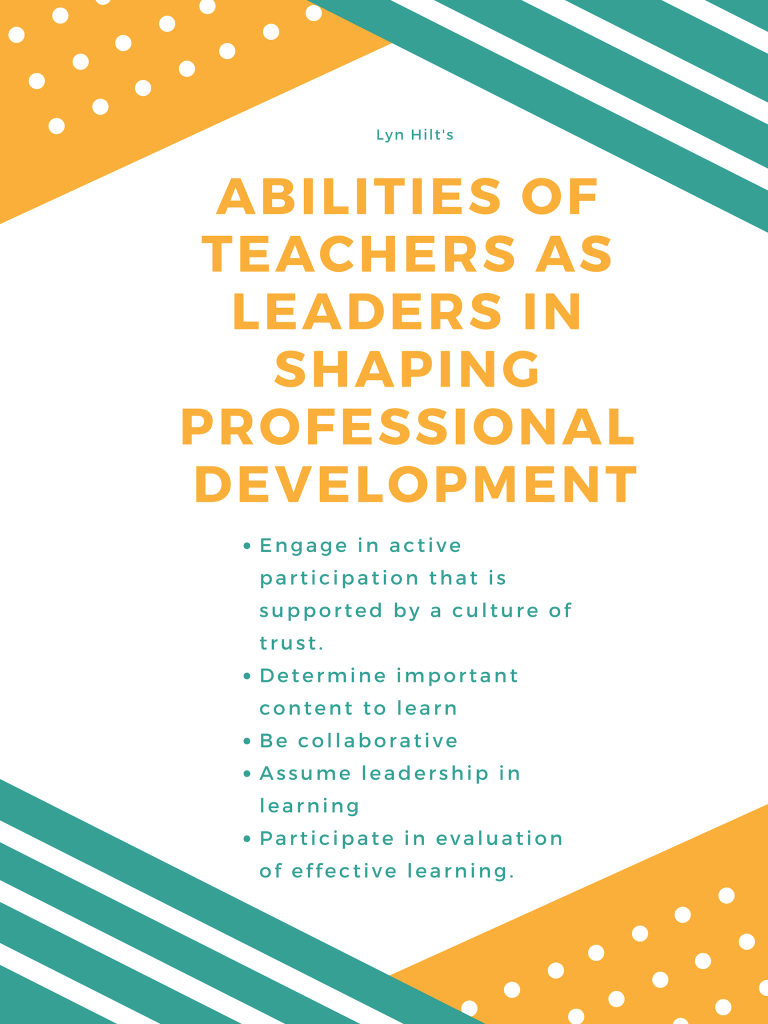

Both Grady and Hilt agree that building community and shared experiences are key to successful professional development. Grady offers the “teacher-to-teacher” model where technology modeling takes center stage. In this model, teachers demonstrate learning activities to other teachers (their audience) while allowing their audience an opportunity to explore and implement these activities, (Grady, 2011). While it may seem that the role of the administrator in this model is minimal, successful implementation is dependent on allowing teachers opportunities for repeated activities as this model does not work well in isolation. In addition, administrative support is crucial by providing key resources and time to practice the skills learned in each “teacher-to-teacher” session, (Grady, 2011). While Grady’s model fosters community through localized support, Hilt emphasizes community and collaborations supported through professional learning communities (PLCs) that represents a broad network of professionals learning from each other in addition to the local resources. In the PLC model, teachers are viewed as experts and therefore are afforded active participation and choice in professional development. Hilt offers several characteristics of teachers as experts as summarized in figure 1.1 below.

In both of these models described above, the teachers are in control of the learning itself while administrators support that learning. As established, successful implementation of professional development, or learning, relies on the administrators’ ability to establish a clear vision, communicating that vision while modeling good technology practices, and finally providing resources. When teachers are allowed an active role in an environment that supports on-going learning and fosters community, learning that shapes teaching occurs.

Resources

Grady, M. (2011). Principle’s roles as technology leader. Available from: https://www.seenmagazine.us/Articles/Article-Detail/articleid/1800/the-principal-8217-s-role-as-technology-leader

Hilt, L. (2011). Out with professional development, in with profession learning. Available from: https://plpnetwork.com/2011/08/18/out-with-professional-development-in-with-professional-learning/