It shouldn’t be a surprise that experts support the idea of incorporating technology into new and existing learning models to facilitate deeper and different skill sets than those taught by conventional methods today. The biggest push for more technology adoption in education is to move the educational system away from antiquated models developed during the industrial revolution to a system that reflects today’s society and workplace. I particularly enjoy Sir Ken Robinson’s argument for changing the education system because we are living an an era where we are trying to meet the needs of the future with old methods designed for a different society than the one we live in now, (RSA, 2010). Robinson stresses that we need to adopt new models that redefine the idea of “academic” versus “non-academic” and accept differences in thinking in regards to what it means to be “educated”. Part of the reason for this push is that today’s children are exposed to information stimuli which capture attention and change learning needs, (RSA, 2010).

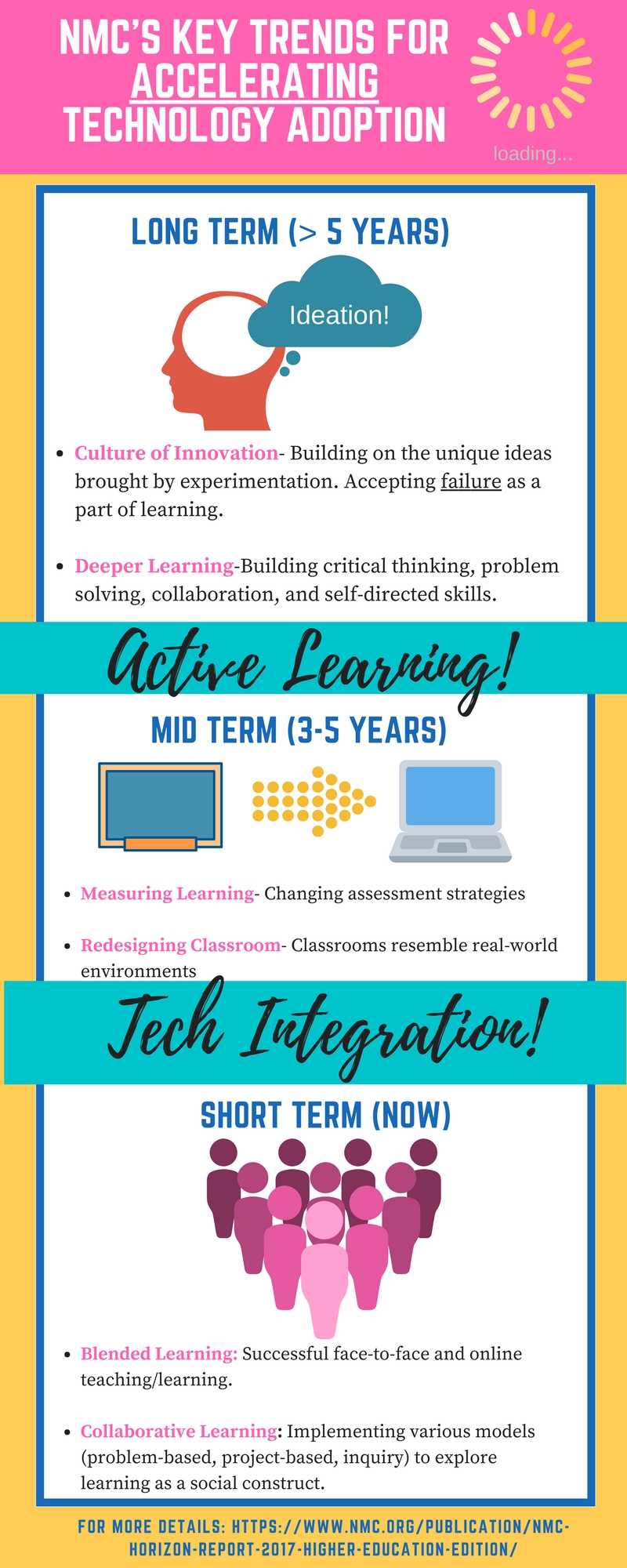

Incorporating 21st century skills requires introduction, implementation, and use of technology at all levels of education. Considering the importance of developing these skills, it is also important to understand the reasons behind creating a paradigm shift, particularly as we prepare students for the real-world in higher education. The New Media Consortium (NMC) published a report looking into the key trends that would promote and accelerate technology adoption in higher education. NMC identified and classified these trends in terms of length of time needed for implementation as well as difficulty, (NMC, 2017). Figure 1.1 summarizes the six key trends for technology adoption.

What’s interesting to note about the trends above is that they not only focus on types of technology, or ways that technology is used in the classroom, but also on important skill sets and new ways of thinking that elevate technology use to a different, more meaningful level.

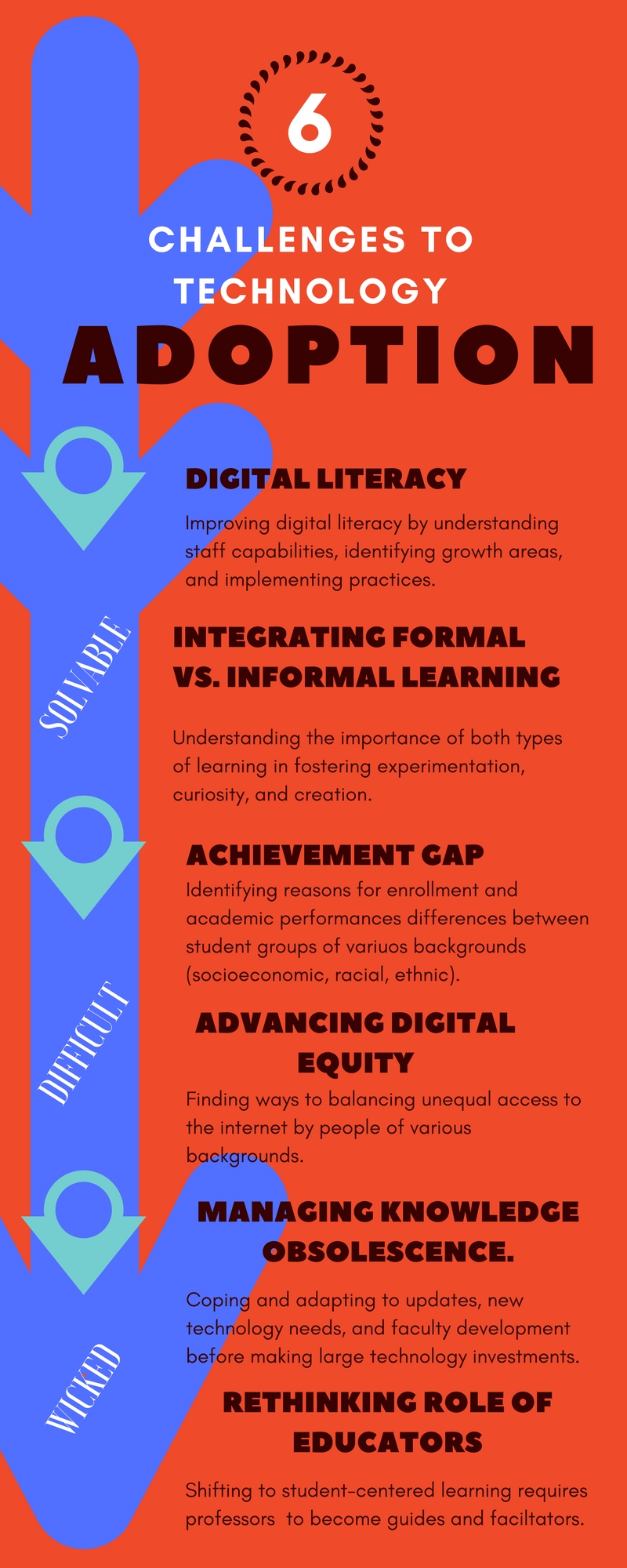

Because the primary responsibility of a higher education institution should be to prepare students for the real-world, understanding the technology implications behind each of these trends call us, the professors, to reevaluate our technology use in the classroom. Despite these conversations on the need for technology adoption in higher education, several challenges continue to slow the rate of adoption. NMC summarized six key challenges that significantly impede the process of the aforementioned trends. The challenges were classified from “solvable”, meaning the problem is well understood and solutions exist, to “wicked” where the challenges involve societal change,or, dramatic restructuring of thinking or existing models, where solutions can’t be identified in the near future, (NMC, 2017). Figure 1.2 describes these challenges in more depth.

While experts look into the challenges that require more investigation and assessment of impact, I’d like to focus on one of the solvable challenges: digital literacy. Digital literacy has a broad definition which include a set of skills that “… fit the individual for living, learning, and working in a digital society,” (JISC, 2014). While mostly thought of as the ability to use different types of technology, the definition expands to include a deeper understanding of the digital environment, (NMC, 2017). Successful components of digital literacy include accessing, managing, evaluating, integrating, creating, and communicating information in all aspects of life, (UNESCO, 2011). The UNESCO Institute for Information Technology in Education argues that digital literacy is basic skill that is equally as important as learning to read, write, and do math, (UNESCO, 2011). Interesting, when students are taught digital literacy and are allowed to use technology in learning, they grasp math and science more readily and easily than students without this skill, (UNESCO, 2011).

While it is clear that digital literacy is an important skill, during a departmental assessment conducted for another class, digital literacy was one of the biggest impediments to adopting technology. Faculty were only adopting technology only in response to industry need. Many professors were eager to learn but not sure how to start using new technology, while others simply did not see a value in spending time and energy in implement new learning methods. Among the biggest barriers explored were time, knowledge deficit, and lack of professional development on digital literacy. Therefore, improving digital literacy will prove to be crucial to promote more tech adoption in the classroom. Professional development would need to include a conversation on what literacy looks like for each discipline and should not only include online etiquette, digital rights and responsibilities, curriculum design built around student-facing services, but also on the incorporation for the right technology for each context, (NMC, 2017).

The ISTE standard for educators (2c) states that modelling is the, “identification, exploration, evaluation, curation and adoption of new digital resources and tools for learning” that can be used in professional development, (ISTE, 2017). So the what are effective methods for modeling and facilitating good digital literacy as part of faculty (formal or informal) development?

Peer modeling has been suggested as an alternative to traditional professional development or inservice. Among the reasons for peer modeling success is the fact that peer modeling is personalizable and actionable. Faculty can choose the various digital literacy topics they are personally interested in, receive one-on-one training related to their knowledge gap and needs while receiving hands-on application, (Samek, et. al, 2016). George Fox University piloted a peer modeling project after reviewing key data related to a digital fluency mentorship program that utilized tech solutions and the pedagogy to support tech use). The program was initially developed to address faculty desire for one-on-one training. From faculty feedback survey, the program developers learned that faculty are more likely to adopt a tech solution if they see it in action (actionable examples) and are given evidence of positive student learning outcomes. Due to the success of the program, the university has expanded its efforts to other collaborative development, (Samek, et. al. 2016).

Learning from George Fox’s example, universities could build resources to offer similar professional development on digital literacy to improve technology adoption. What I particularly like about this idea is that it is a different way to look a professional development where the mentor can be the expert but it could also later transition into a co-learning model to increase ownership and interest in technology adoption. This model goes beyond professional development to focus on the real-time needs of each faculty member and work on existing classroom components. Above all, peer modeling improves digital literacy to increase technology adoption to further develop the 21st century skills of students and teachers alike.

References

JISC, (2014, Dec. 16). Developing digital literacy. [website]. Available from: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developing-digital-literacies.

New Media Consortium, (2017). Horizon report: 2017 Higher Education. [pdf]. Available from: http://cdn.nmc.org/media/2017-nmc-horizon-report-he-EN.pdf

RSA, (2010, Oct 14). Changing educational paradigms [Youtube Video]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDZFcDGpL4U.

Samek, L., Ashford, R.M., Doherty, G., Espinor, D., Barardi, A.A., (2016). A peer training model to promote digital fluency among university faculty: Program component and initial efficacy data. Faculty Publications, School of Education. Paper 144. Available from: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1143&context=soe_faculty

UNESCO Institute for Information Technology in Education, (2011, May). Policy brief. [pdf]. Available from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002144/214485e.pdf