Building 21st century skills is the imperative focus for most educational institutions. Many education articles and blog posts are centered around techniques and concepts that educators can use to develop these skills in their students. Yet what about an educator’s need to build these skills? How can educators learn and gain 21st century skills before teaching and modeling them in the classroom? One proposed method is to provide more professional development to help educators build these skills, but now many researchers argue that traditional presentation-only professional development sessions leave little room for implementation. An early study conducted by Showers and Joyce found that only ten percent of professional development participants implemented what they learned into the classroom. When educators were allowed to practice what they had learned, implementation increased drastically, (Showers & Joyce, 1996).

What Showers and Joyce were researching was the concept of “peer coaching.” Peer coaching is a professional development strategy in which colleagues spend time in a collaborative environment working towards improving standard-based instruction and support efforts for building 21st century skills, (Foltos, 2013). Peer coaching may take on many forms but usually includes a collaborative process in which the teacher leader assists in co-planning activities, models strategies and techniques, provides observation of teaching and reflection, while avoiding formal evaluation of the peer, (Foltos, 2013). Through peer coaching, the collaborating pair begin to build a culture of standards and expectations, increase instructional capacity, support ongoing evaluation, and create a platform for connecting teaching practices to school policies, (NSW Department of Education, 2018). Student learning benefits when teachers learn, grow, and change through peer coaching, (Showers & Joyce, 1996).

The ISTE standard for coaches defines a peer coach’s role: as “contribut[ing] to the planning, development, communication, implementation, and evaluation of technology-infused strategic plans at the district and school levels,” (ISTE, 2017). Therefore, understanding peer coaching best practices is important to effective coaching. Since the coach’s role is to take part in the planning, implementation, and evaluation cycle, I began wondering about effective time spent in coaching sessions with a peer. This wonderment stems back from my past role as a nutrition counselor. One of the biggest issues that would come up concerned the appropriate length of a counseling session. Medical insurance allowed for billing in fifteen-minute increments though fifteen minutes was hardly enough time for any successful progress to take place. There was distension among professionals about whether 30 minutes or one hour was more effective. My former employer insisted that every session should be a minimum of one hour, which felt appropriate for first, second, and sometimes even third session, yet felt unnecessarily long after about the fourth session. I often wondered at what point is there too much information given, in comparison to too little, for a coaching session to be effective? Now as I step into the role of a technology coach, these same questions enter my mind, what is a reasonable timeframe for peer coaches to fulfill their roles (i.e. how long would a coaching cycle take)?

My questions, as it appears, do not have a straightforward answer. A program called “Incredible Years” offers some guidelines into actual number and timeframes, citing that one-hour coaching sessions should occur after every two or three teaching lessons particularly if the educator is new to the program. More experienced educators may meet less often. Despite these very specific guidelines, the program designers state that the guidelines serve as recommendations at best, (Incredible Years, n.d.).

Researchers and educational leaders agree that coaching, regardless of its medium, is an individualized process. According to educational leader, Les Foltos, peer coaching needs to be personalized to be effective. One of the hallmarks of a good peer coach is making the process manageable for the coaching partner, (Foltos, 2013). Time spent on improvement will be dependent on other time obligations, such as current workload. Rather than focusing on a fixed time minimum, Foltos recommends that the time set out for coaching should be based on the peer’s capacity and readiness for improvement, (Foltos, 2013). In fact, peer coaching may never have a clear resolution time but rather it may be a cyclical process. The key to understanding the process length will lie in continual reflection and evaluation of the coaching goal(s), (Foltos, 2013).

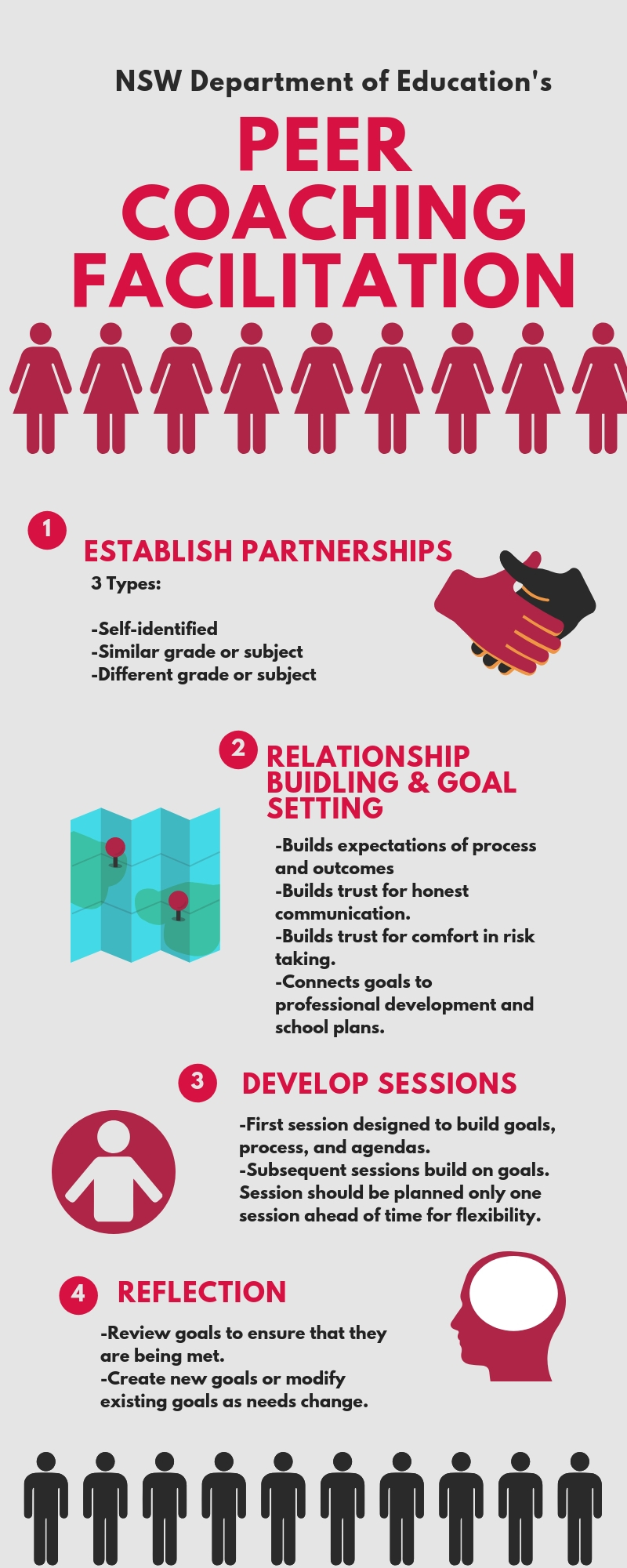

Foltos isn’t the only educational leader to suggest the long-term nature of peer coaching, the NSW Department of Education defines peer coaching as a “long term professional development strategy,“ (NSW Department of Education, 2018). Like Foltos, the NSW suggests a cyclical nature to peer coaching as outlined in figure 1.1 below.

The peer coaching cycle is dependent on relationship development and trust building that supports open, honest communication and comfort with risk-taking. Once these relationships have formed, the coaching process can be ongoing because professional development needs and goals change. The length may also be naturally determined as many teachers choose to continue the collaboration process even after the initial goal has been met, (Showers & Joyce, 1996). There is congruence among researchers that length of peer coaching session is less important than the process that is followed. Initial peer coaching sessions should focus on relationship building in which both parties share goals, agree on the coaching process, and establish agendas with topics to explore. A good peer coach would help their collaborative partner establish SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, timely) goals that help them build a personalized timeline for meeting their joint objectives, (NSW, 2018). Once this process has been followed, any sequent sessions should allow for flexibility and reflection, ensuring its ongoing nature, (NSW, 2018).

Though there are many similarities in nutritional and technology coaching, the timeline needs are vastly different. In both instances, the relationship development between a coach and their partner is crucial for success. Open, honest communication and risk taking does not readily occur without a safe and established relationship. However, in technology coaching, the idea is to work with a peer, not a client, to build a collaborative partnership that is long lasting and transcends any initial short-term goal.

Resources

Foltos, L., 2013. Peer Coaching: Unlocking the Power of Collaboration. Chapter 1: Coaching roles and responsibilities. Corwin Publishing. Thousand Oaks, CA.

Incredible Years, (n.d.) IY peer coaching expectations. Available from: file:///C:/Users/Catalina/Downloads/Peer-Coaching-Dosage-8-16%20(1).pdf

ISTE, (2017). ISTE standards for coaches. Available from: https://www.iste.org/standards/for-coaches

NSW Department of Education, (2018). Peer Coaching [website]. Available from: https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/curriculum/learning-for-the-future/Future-focused-resources/peer-coaching

Showers, B., Joyce, B., (1996). The evolution of peer coaching. Available from: http://educationalleader.com/subtopicintro/read/ASCD/ASCD_351_1.pdf