Alan Alda, from M*A*S*H*, knows how to tell a story. In one of his presentations, he asks a young woman to the stage. Alda then asks the young woman to carry an empty glass across the stage. She stares at the him awkwardly and does it without much fanfare. Alda then walks to her with a pitcher of water. He pours water into the empty glass and fills to the brim. He asks her to carry the glass to the other side of the stage. “Don’t spill a drop of water or your entire village will die.”- he says. The young woman, slowly, deliberately walks across the stage. She carefully gauges the level of water in the glass as she takes each step. The audience is silent, enraptured in the backstory of the overfilled glass. They are interested and invested in the story. (Watch Alan Alda explain the importance of storytelling in his video: “Knowing How to Tell a Good Story is Like Having Mind Control.”)

Stories are powerful. Storytelling is one of the oldest forms of communication that we have. We are attracted to stories because they are human, (Alda, 2017). Stories relay information about human nature, accomplishments, challenges, and discoveries. They make us feel part of a community and help evoke empathy, (Dillion, 2014). According to Alan Alda, we like stories because we think in stories, particularly if the story has an obstacle. Like in the example above, we are interested in listening to the attempts overcoming the obstacle, (Alda, 2017).

Stories can also be powerful in the classroom. A good story helps shape mental models, motivates and persuades others, and teaches lessons, (Dillion, 2014). There are many ways to deliver a story but I have been gaining significant interest in digital storytelling. Technology is not stoic but rather highly personalizable as people are discovering unique ways to learn, entertain, network, and build relationships using technology, (Robin, 2008). It is not surprising then that people are using technology to also share their story. Digital storytelling is technique that I discovered as I was exploring problem based learning (PBL) to develop innovation skills. In that blog post, I explained that digital storytelling was one mode students could employ to “solve” a problem in PBL by creating an artifact. I realize that this wasn’t directly related to my inquiry at the time, because problem-based learning is more focused on the process of problem-solving rather than the artifact itself. Despite this, I found the idea of digital storytelling interesting and wanted to revisit it. “Storytelling” in particular, is a buzzword that circles back in unexpected mediums. For example, my husband attended a conference that explored storytelling through data, in other words, how to design graphs, charts, and other visual representations of data that share a story without any significant description or explanation. Yet these graphs communicate important information. That then got me pondering about how digital storytelling can be used to teach students to creativity communicate information either about themselves or about a topic using technology.

So then how can students use digital storytelling for the purposes of creative communication? This question relates to ISTE Student Standard 6: Creative Communicator in which, “students communicate clearly and express themselves creatively for a variety of purposes using the platforms, tools, styles, formats and digital media appropriate to their goals.” Digital storytelling is one vehicle in which students can use to express and communicate clearly. Interestingly, the idea of digital storytelling isn’t new, it was originally developed in the 1980’s but is experiencing a renaissance in the 2000’s, (Robin, 2008). Not only can digital storytelling be a medium for learning, but also different types of information can be relayed using this technique including personal narrative (what most non-ed professionals use), stories on informing/instructing, and lastly, stories that examine historical events, (Robin, 2008).

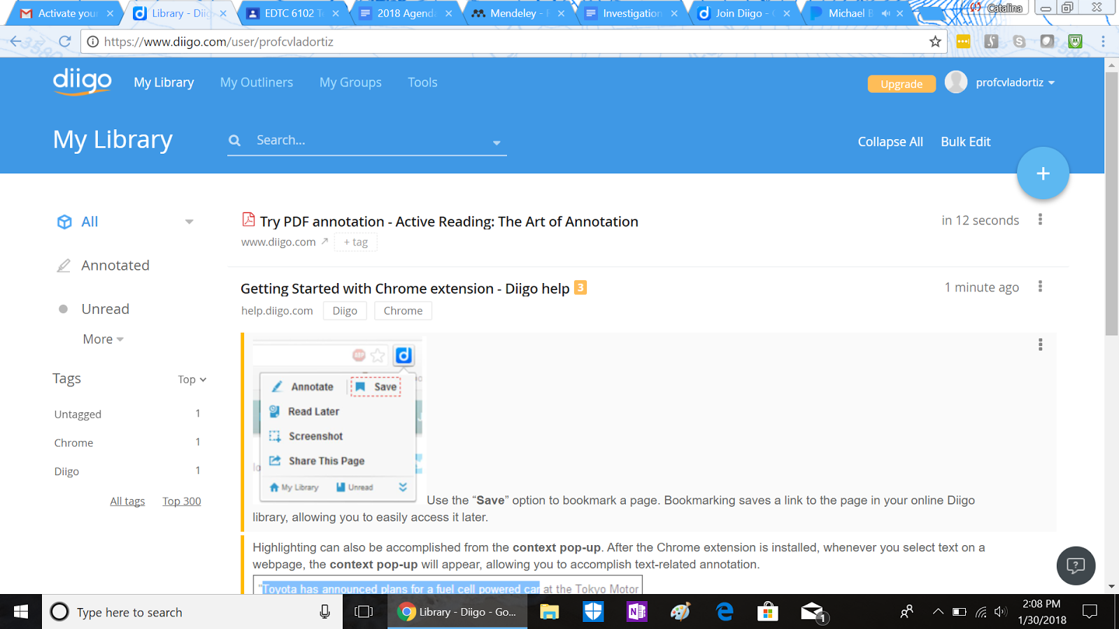

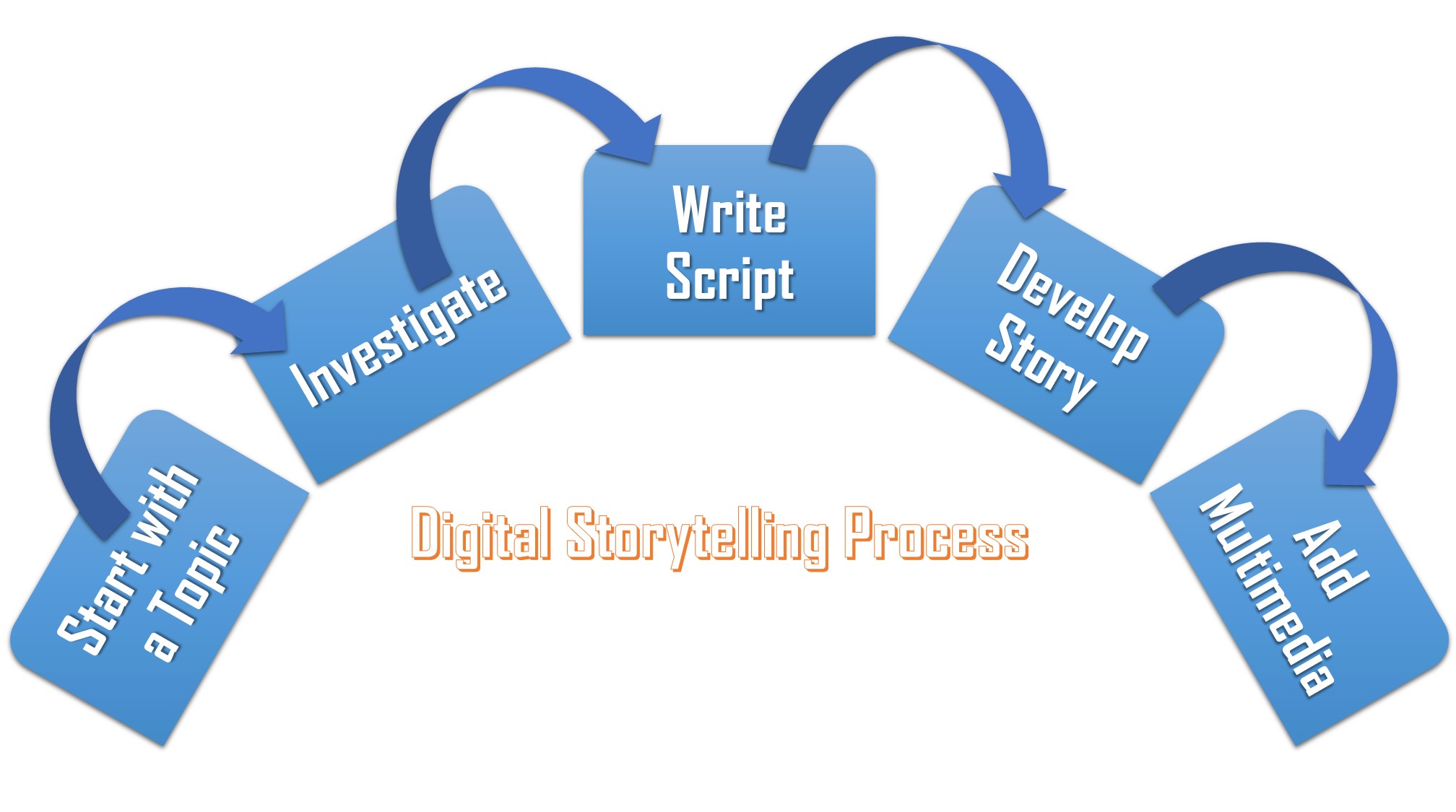

Stories must be well-crafted in order for them to be effective and memorable. Students can deliver a story by investigating a topic, write a script, develop their story, and tie it all together using multimedia, (Robin, 2008). Blogs, podcasts, wikis, and other mediums like pinterest can be used to convey a story simply,(University of Houston, 2018). To help students get started, the University of Houston’s Educational Uses of Digital Storytelling webpage offers great information such as timing, platforms, and examples of artifacts.

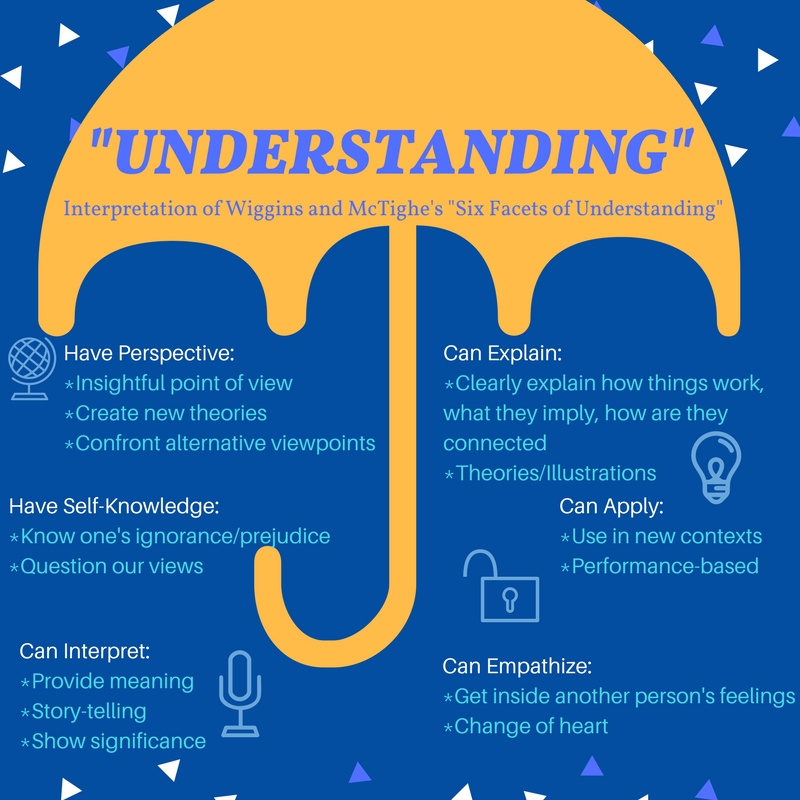

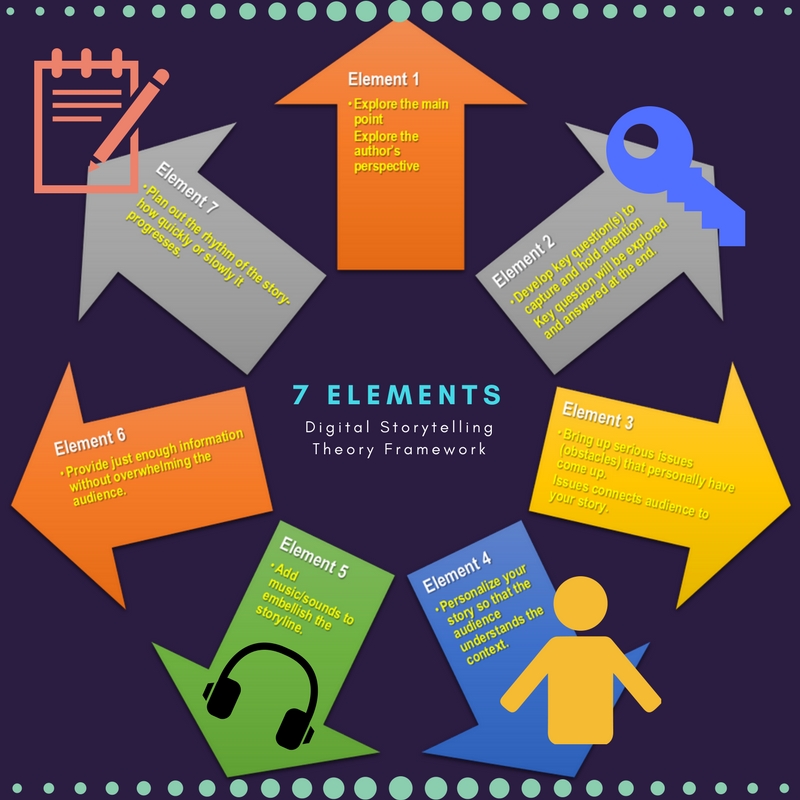

Before diving into a story, the most important elements are explored in its theoretical framework. This framework includes the seven-elements needed in order for each story to be impactful. Figure 1.2 below summarizes the seven key elements.

Just as Alan Alda explores in his video, the seven-elements emphasize that good stories must capture the audience’s attention, explore obstacles or serious issues that the audience can connect with, and must be personal in order to enhance and accelerate comprehension, (Robin, 2008). By allowing students to engage in digital storytelling, they are also developing crucial 21st century skills: digital, global, technology, visual, and information literacy.

Tying it all together: How does digital storytelling fulfill the requirements for the ISTE student standard on creative communicator?

As Robin alludes to, it can be challenging to distinguish the various types of stories because oftentime they overlap, particularly considering the personal narrative, (Robin, 2008). A good story is relatable, we can put ourselves into the shoes of the protagonist. The use of technology is just another medium we can use to communicate our stories. By implementing digital storytelling in the classroom, it would allow for transformation (SAMR) of existing assignments and lectures. Here are some additional thoughts on how this technique can help students become creative communicators:

- ISTE 6A: “Students choose the appropriate platforms and tools for meeting the desired objectives of their creation or communication”. Platforms such as blogs, podcasts, in addition to tools such as cameras, and editing software are all components of digital storytelling. Allowing students to evaluate the various platforms and tools in relation to their desired outcome, they would be developing digital, technology, and visual literacy.

- ISTE 6B: “Students create original works or responsibly repurpose or remix digital resources into new creations”. Though the most common application of digital storytelling would be to create an original artifact, Robin provides an example of remixing in recreating historical events by using photos, or old headlines to provide depth and meaning to the facts students are learning in class, (Robin, 2008). By curating and remixing existing artifacts, students would develop global, digital, visual, and information literacy.

- ISTE 6C: “Students communicate complex ideas clearly and effectively by creating or using a variety of digital objects such as visualizations, models or simulations”. This idea goes back to the example I shared of storytelling using data (graphs/charts/figures) but it can also include infographics. Depicting complex data through an interesting visual medium engages digital, global, technology, visual, and information literacy.

- ISTE 6D: “Students publish or present content that customizes the message and medium for their intended audiences”. The basis of storytelling is that it is meant to be shared with others. If the story doesn’t match the audience, it will not be impactful or important. This is a point the 7-elements of digital storytelling stresses. Understanding and crafting stories for a specific audience demonstrates digital and global literacy.

Good digital storytelling can allow students become creative communicators. Using technology can reach audiences in many ways never thought of before while still sharing the human experience. As Robin puts it, in a world where we are receiving thousands of messages a day across many different platforms, stories become engaging, driving, and a powerful way to share a message in a short period of time, (Robin, 2008).

Resources

[big think channel]. (2017, July 18). Knowing how to tell a good story is like having mind control: Alan Alda. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r4k6Gm4tlXw

Dillon, B. (2014). The power of digital story. Edutopia. Retrieved from http://www.edutopia.org/blog/the-power-of-digital-story-bob-dillon

International Society for Technology in Education, (2017). The ISTE standards for students. Retrieved from: https://www.iste.org/standards/for-students.

Robin, BR., (2008). Digital storytelling: A powerful technology tool for the 21st century classroom. Theory into Practice, 47: 220-228. DOI:1080/00405840802153916

University of Houston, (2018). Educational use of digital storytelling. Retrieved from: http://digitalstorytelling.coe.uh.edu/page.cfm?id=27&cid=27&sublinkid=75