Coaching culture is prevalent in the business world. Simple internet searches on the topic offer many articles and resources providing suggestions to build a stronger culture on the corporate scale. In these articles, managers are called to encourage coaching through shared experiences and incentivize employees to successfully participate. In education, peer coaching has established itself as a useful and resourceful form of professional development in K-12 schools. Peer coaching is so highly esteemed that the Department for K-12 Public Schools in Washington State offers educational grants to support peer coaching. Yet in the higher education world, peer coaching is still in nascent stages. University professors Victoria Scott, and Craig Miner explore peer coaching use in higher education and claim that only 25% of institutions use it as a way to stimulate innovation and improvement, (Scott and Miner, 2008). Even among institutions that employ peer coaching, peer observation was among the most widely used method. This is true for my higher education institution. Every year faculty complete a Professional Development Plan (PDP) in which the faculty member addresses needs for improvement, innovation, and training. One of the required components for completing the PDP process is to participate in a classroom observation by a peer and receive feedback. While observation can be a form of peer coaching, the observers oftentimes are not trained as coaches and these conversations tend to explore course content and audience engagement only. Learning outcomes, active learning, and 21st century skills are largely ignored. Scott and Miner acknowledge that this form of peer evaluation isn’t new in higher education but can be limited because it is one-sided and short-term, (Scott and Miner, 2008).

As I reflect back upon my experience in peer coach training, I realize that there currently isn’t a system in place for me to continue my work as a peer coach outside of isolated events. Outside of my personal desire to continue using my peer coaching skills, ISTE also encourages this through its sixth coaching standard highlighting the importance of continuous learning to improve professional practice. The standard states that coaches “engage in continuous learning to deepen professional knowledge, skills, and dispositions in organizational change and leadership, project management, and adult learning to improve professional practice,” (ISTE, 2017). Reflecting on this call to action, I began wondering how to embark of organizational change to develop a peer coaching culture in higher education.

Barriers to establishing peer coaching culture.

Coaching creates an innovation culture where the team is responsible for solving complex problems and supports accountability, (Brooks, n.d.). In higher education, it allows a department to improve collegiality and provide moments of reflection necessary for critical discourse to occur, (Scott & Miner, 2008). Despite the benefits of promoting a peer coaching culture, no sooner did I start investigating culture implementation did I run into potential barriers to culture change. Of the various reasons why an institution may not be receptive to peer coaching, lack of vision, isolation, and lack of confidence in collaboration efforts, were among the top barriers, (Slater & Simmons, 2001).

Lack of vision. Current institutional culture dictates success of peer coaching initiatives. Institutions with short-term goals and/or top-down management styles do not provoke qualities necessary for good peer coaching culture as it requires support from administrators, (Brook, n.d.). Administrators not only give approval for peer coaching to take place, but are also vocal in its promotion, participation, and long term viability, (Brook, n.d.). Misconceptions and lack of understanding in the value of peer coaching lead to poor administer buy-in. When administrators view coaching as “time-wasting” or valued as a remedial action, its potential is diminished. This ignores large benefits such as attracting and maintaining top talent, promoting constant innovation, maintaining intrinsic motivation and workplace satisfaction for all, (Brook, n.d.). The lack of vision may not spark from misconception but rather lack of awareness or a knowledge deficit about peer coaching. Administrators without previous exposure to coaching may have trouble envisioning the process, may have logistical questions, or worry about potential negative outcomes of peers observing one another for the purpose of growth and development, (Barnett, 1990).

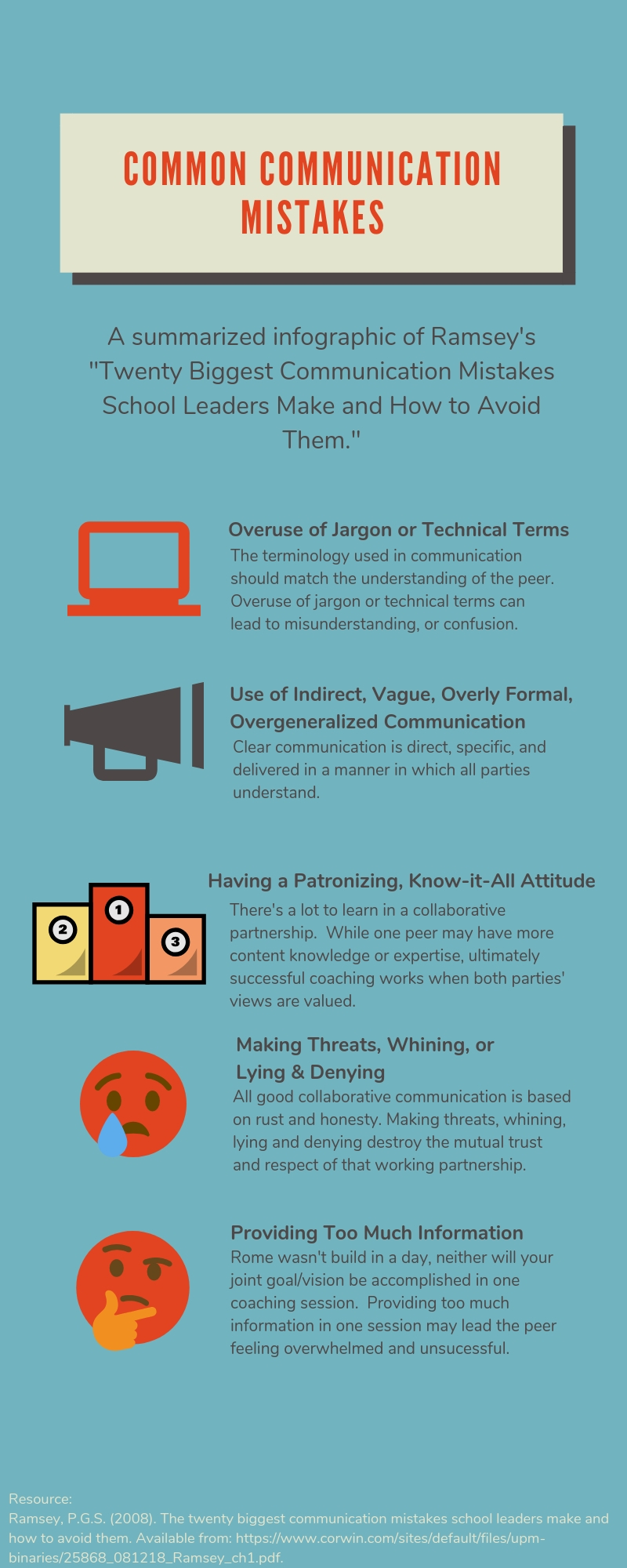

Professors tend to work in isolation. Professors Victoria Scott and Craig Miner recognize that peer coaching has not been more readily implemented in higher education because professors work autonomously, independently trying to achieve improvement and innovation through the scholarship of teaching, (Scott & Miner, 2008). There is fear that collaboration may remove the academic freedom that professors are rewarded, leading to strict and rigid changes in teaching, (Scott and Miner, 2008). Another significant barrier for professors is the perceived lack of time. In order for peer coaching to be successful, the assumption is that peer coaching efforts are long-term and on-going. Given other commitments and required scholarly activities, even if a professor has the intention to participate, actual follow-through is lacking (Scott and Miner, 2008). Professors also fear that their peer coaching efforts will not be rewarded or recognized by their institution, particularly if current policies on promotion do not support such efforts. Scott and Miner argue, however, that peer coaching has been linked to improved course evaluations which are used for tenure and other promotion efforts, (Scott and Miner, 2008).

Lack of confidence in collaboration. Confidence needs to be instilled through better understanding of the peer coaching process. Scott and Miner define peer coaching as a “confidential” process in which both parties hold no judgement but rather build a relationship on collaborative and reflective dialogue, (Scott & Miner, 2008). “No one grows as a leader without the support of others,” (Friedman, 2015). Peer coaching works because building trust and rapport is an essential component to the process. Innovation and change happen quickly because peer coaching makes partners honest about goals, hold each other accountable, and creates actionable tasks leading to better and more effective outcomes, (Friedman, 2015).

The lack of confidence can also stem from inadequate peer coaching training. This can result largely from institution resource allocation. However, continued peer coaching training does not have to rely on monetary resource only but also recognize that outside sources can be used to support additional training such as social networks and the establishment of Professional Learning Cohorts (PLCs), (Brook, n.d.)

Institutional implementation of peer coaching culture.

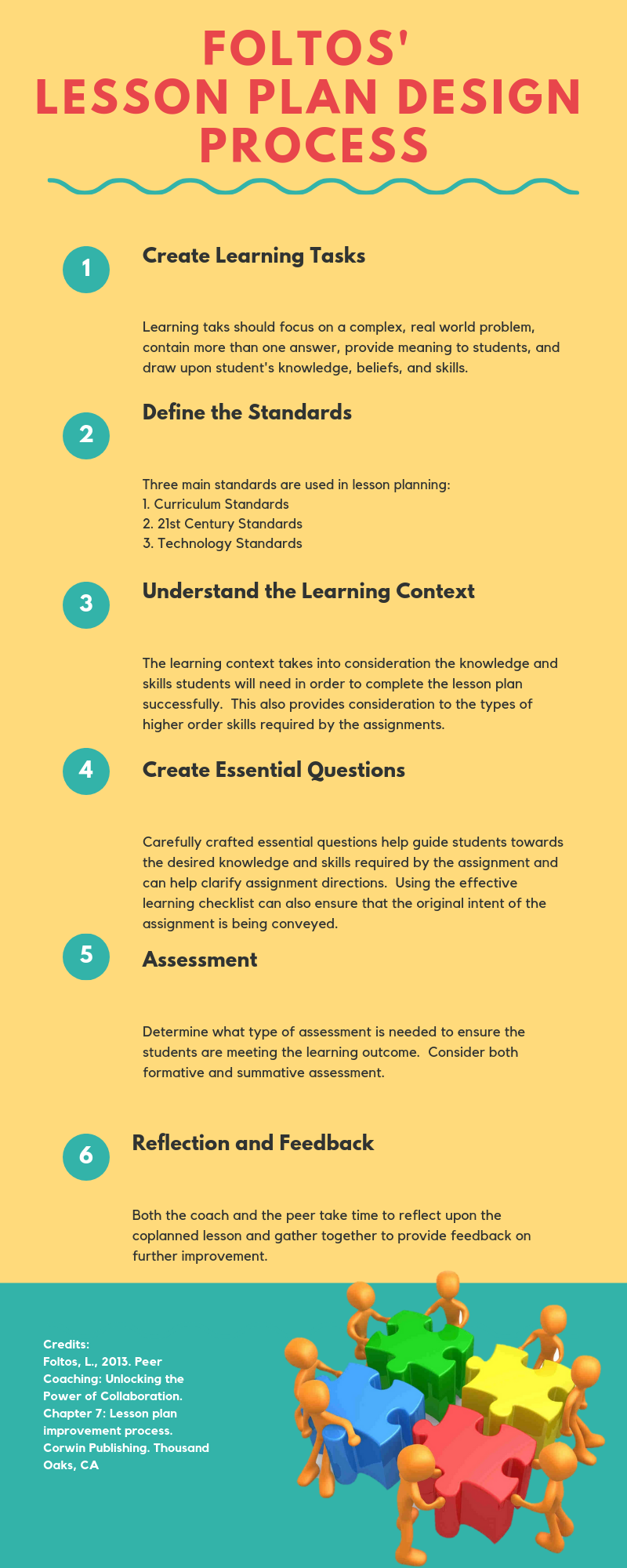

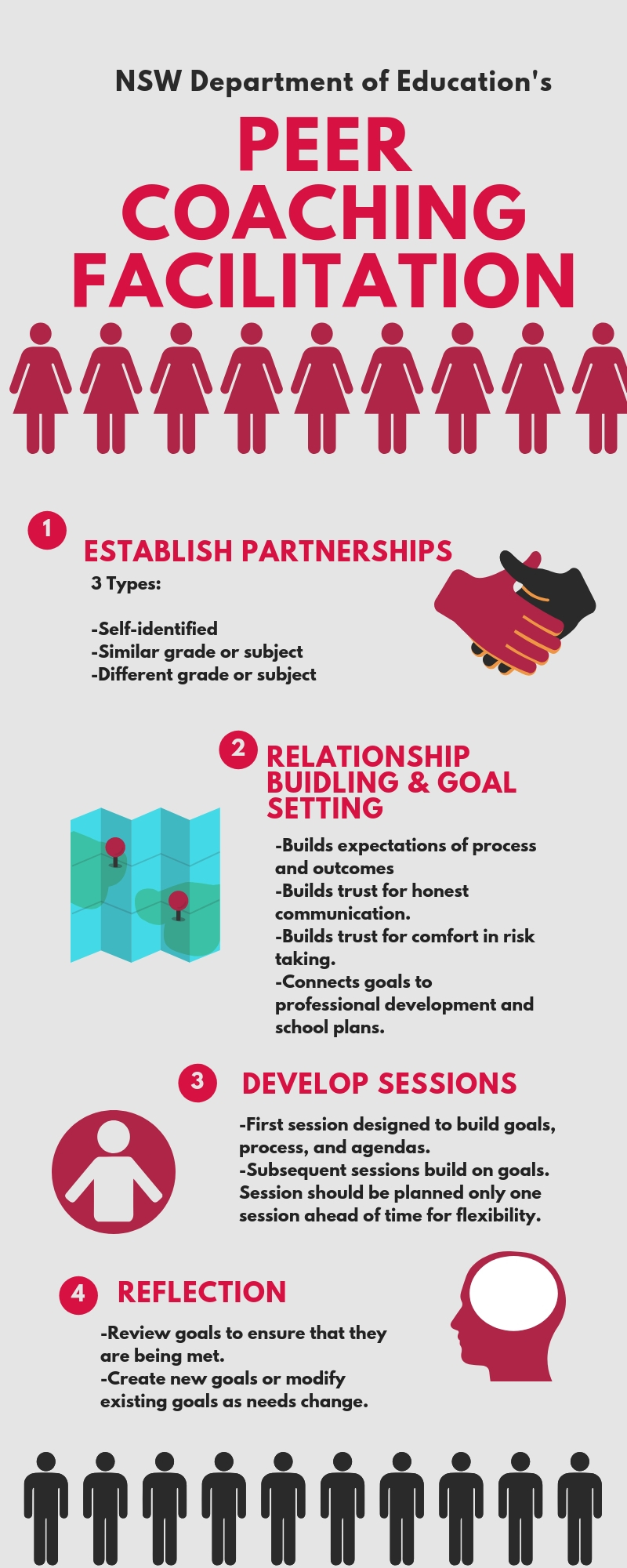

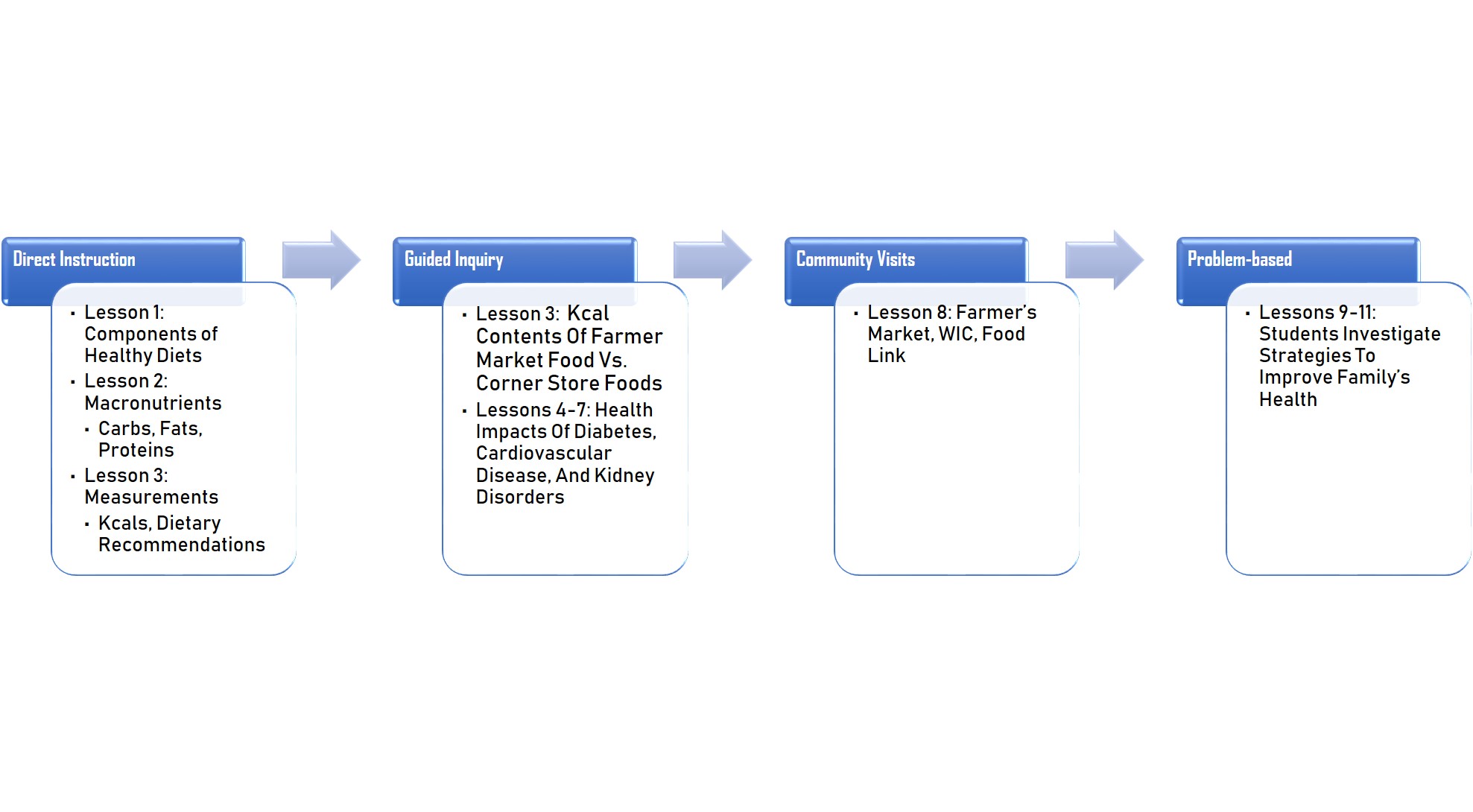

“When good coaching is practiced, the whole organization will learn new things more quickly and…adapt to changes more effectively,” (Mansor et. al., 2012). Coaching can serve as a catalyst for change on multiple levels of an institution. Department chair, professor, and educational leader, Barbara Gottesman, has been working to establish peer coaching in university settings since the nineties. Her book, “Peer Coaching in Higher Education,” highlights numerous case studies in which peer coaching cultures have not only helped enrich the learning environment but also helped address several of the barriers listed above. Dr. Gottesman argues that successful coaching culture only functions when specific rules and concepts are in place and all stakeholders adhere to the process, (Gottesman, 2009). Figure 1.1 provides a summary of Dr. Gotteman’s peer coaching process.

Drawing from the recommendations from Dr. Gotteman, and additional business and coaching leaders, the following are summarized determinants of a successful peer coaching culture:

- A strong link between organizational strategy and developmental focus. The alignment of professional development with tangible organizational goals is the strongest indicator of peer coaching culture adoption. For an organization, one supports a means for achieving the other, (Mansor, et.al, 2012). In order to do this, coaching leaders recommend performing a culture assessment which addresses this link. The assessment should focus on attitudes and understanding of peer coaching, along with the institution’s mission, value statements, vision, and a review of the current policies in place that may support or inhibit peer coaching practice, (Leadership That Works, n.d).

- Administrative commitment. Strong administrative commitment supports proper implementation and addresses resistance to change. In order to overcome barriers, administrators hold the responsibility for culture promotion and encouragement. Resistance to change should be managed in a manner that normalizes the emotional impact, meaning that employees’ concerns and voices are heard, (Leadership That Works, n.d.). In addition to normalizing the fear, coaching consulting firm “Leadership that Works”, recommends identifying early adopters who would slowly begin incorporating others in peer coaching projects. Successes of early peer coaching helps build excitement and alleviates the fear of the unknown, (Leadership That Works, n.d.).

- Sufficient and appropriate peer coaching training. All experts agree that successful peer coaching culture takes time to establish because good peer coaches need to build skills. The initial need of skilled peer coaches can be met through the use of external coaches that can provide an outside perspective, training, and build innovation, (Leadership That Works, n.d.). Once successful initiation has taken hold, internal coaches can be deployed to further the work. In fact, internal coaches are often more impactful because of their intimate knowledge of the systems and procedures that are being improved upon, (Leadership That Works). When training internal coaches, Dr. Gotteman and coaching leader John Brooks, argue that complicated peer coaching theories should be reserved for more advanced and skilled coaches. Even basic coaching models can be successful, (Gotteman, 2009; Brooks, n.d.).

- Develop culture of recognition and rewards. Professors Scott and Miner recognize that some reward and recognition should be given to professors that embark on peer coaching projects. However, the rewards must go beyond promotion and tenure. The reasoning behind this, Scott and Miner warn, is that there would be little motivation for senior faculty to participate in project without recognition. Since senior faculty can provide a wealth of experience, faculty buy-in is imperative for peer coaching success, (Scott and Miner, 2008).

- Continual learning and development opportunities. The primary purpose of peer coaching is to serve as professional development with the assumption that is the process is on-going. To support continual learning and development opportunities, constant program evaluation will be important, (Leadership That Works, n.d.).

While full-scale institutional change may take time and effort to employ, small changes at the program or department level may help pave the way for larger changes and benefits. Conversations around culture should involve all key stakeholders to gain perspectives and eliminate resistance to change and the barriers that it creates. Promoting coaching culture works for business, it works for K-12 education, and it can certainly also work for higher education.

Resources

Abu Mansor, N.N., Syafiquah, A.R., Mohamed, A., Idris, N. (2012). Determines of coaching culture development: A case study. Procedia. 40, 485-489. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042812006878

Barnett, B. (1990). Overcoming obstacles to peer coaching for principals. Educational Leadership [pdf]. Available from: http://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/journals/ed_lead/el_199005_barnett.pdf

Brook, J. (n.d.) Common barriers to a coaching culture and how to overcome them. StrengthScope website. Available from: https://www.strengthscope.com/common-barriers-coaching-culture-overcome/

Gotteman, B.L. (2009). Peer Coaching in Higher Education. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Friedman, S.D. (2015). How to get your team to coach each other. Harvard Business Review website. Available from: https://hbr.org/2015/03/how-to-get-your-team-to-coach-each-other

ISTE. (2017) ISTE standards for coaches. Available from: http://www.iste.org/standards/for-coaches

Leadership that works, (n.d.) 7 Steps for developing a coaching culture. Available from: http://www.leadershipthatworks.com/article/5037/index.cfm

Scott, V., Miner, C. (2008). Peer coaching: Implication for teaching and program improvement [pdf.] Available from: http://www.kpu.ca/sites/default/files/Teaching%20and%20Learning/TD.1.3_Scott%26Miner_Peer_Coaching.pdf

Slater, C., & Simmons, D. (2001). The Design and Implementation of a Peer Coaching Program. American Secondary Education, 29(3), 67-76. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.spu.edu/stable/41064432