The search for technology solutions that build 21st century skills to empower students continues with the concepts of “knowledge construction” and “content curation”. The ISTE standards for students defines knowledge construction by the ability of students to, “…critically curate a variety of resources using digital tools to construct knowledge, produce creative artifacts and make meaningful learning experiences for themselves and others”, (ISTE, 2017). This means that students use effective search strategies to investigate meaningful resources linked to their learning, critically analyze information, create a collection of artifacts demonstrating connections/conclusions, and explore real world issues, developing “theories and ideas in pursuit of solutions,” (ISTE, 2017). Unlike any other time in history, students today face an enormous challenge of receiving, processing, and using countless bytes of content per day. Understanding how to decipher useful vs. unuseful, relevant vs. irrelevant, credible vs. not credible information is an incredibly important 21st century skill. Some are even saying that “content curator” and “knowledge constructor” will be job titles of the near future, (Briggs, 2016).

Knowledge construction is a facet of the sociocultural theory using a social context for learning where students develop a better understanding of content through collaboration. Students work together to gather information and develop solutions to real-world problems, effectively forcing students to move past their existing knowledge of the world, (Shukor, 2014). Using real-world problems peaks students’ interest of assignments and allows them to put their own spin on a probable solution. This problem-based model allows educators to promote learning through activities that acknowledge what students already know, consider what students need to know to create a solution, and cultivate ideas to solve the problem, (Edutopia, 2016). To successfully run a problem-based classroom, the focus must shift from evaluation of final products (i.e. correct answers on a worksheet) to evaluation of the process in which the answers were produced and the content that the students cultivated. Because of this, the final product or assignment is more variable from group to group based on the results of the collaborative process, but should reflect knowledge attainment, (Edutopia,2016). Shifting focus to a problem-based learning model has benefits beyond the content that students construct through their group work. Students are exposed to more skills such as planning, monitoring, synthesizing, organizing, and evaluating, (Shukor, 2014 & Briggs, 2016). While content curation may not be the main focus of an assignment, understanding how to arrange information in a purposeful way builds information fluency. According to education leader Saga Briggs, content curation is defined as placing purpose and intention on information that should then be shared (perhaps via social bookmarking), used towards the creation of an artifact or final product, and the content curator should provide their own contribution to the body of work, i.e. provide something of value to their target audience, (Briggs, 2016).

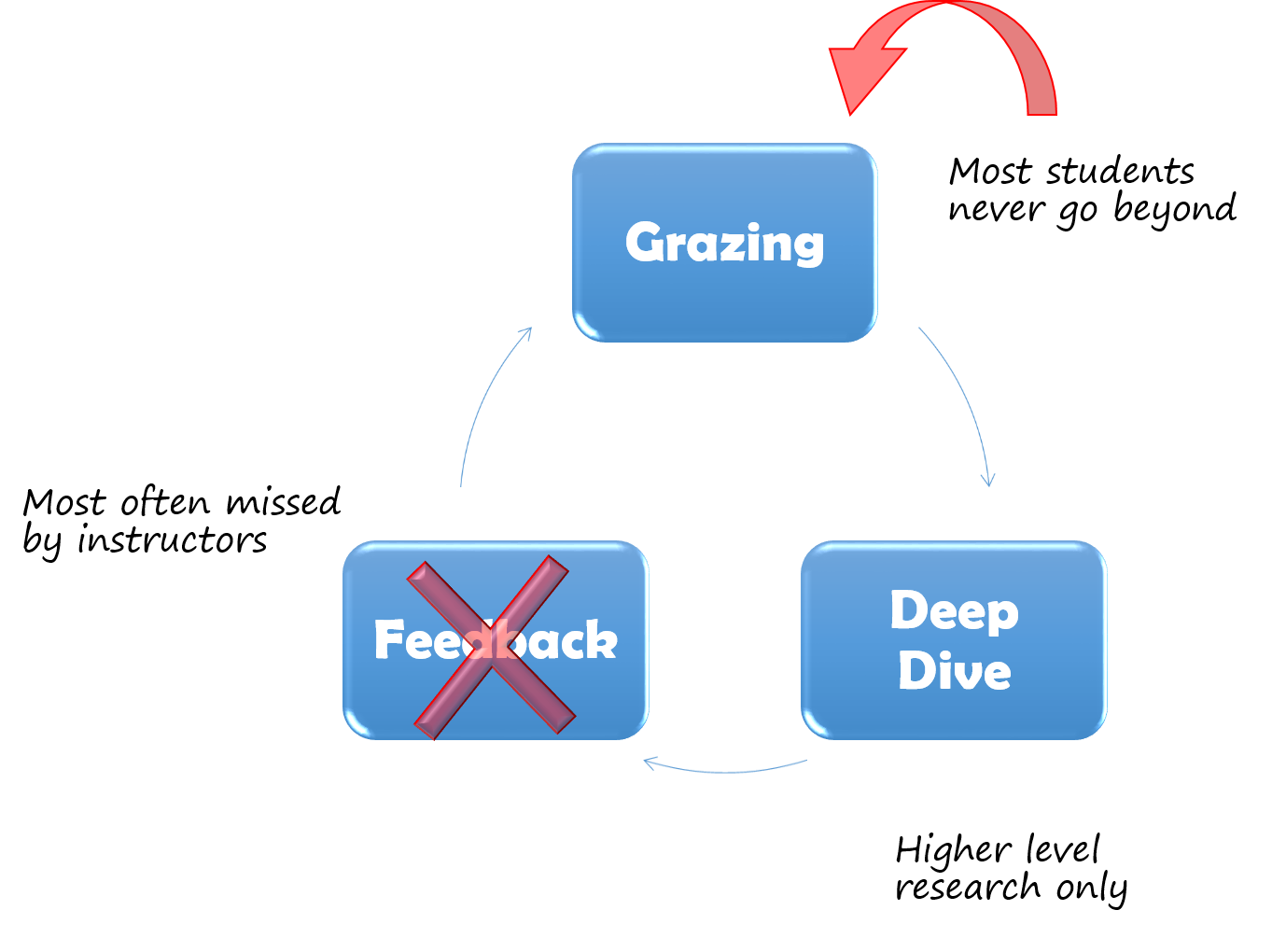

Developing information fluency, or clearly communicating purpose of information, is a key 21st century skill for students. One problem that students face with information fluency is with current student search strategies. Students miss out on the critical analysis portion in information selection, (O’Connor & Sharkey, 2013). It is difficult, or even impossible, to communicate purpose of information without first critically analyzing the information for relevance. Figure 1.1 summarizes O’Connor & Sharkey’s depiction of the current state of student search strategies.

This search strategy depicts a vicious cycle. The educator’s ultimate goal is to get students to conduct higher level investigation (i.e. critical analysis), but most students never move past the “grazing” or the background search. This problem is further exacerbated by educators who do not provide feedback (see my previous post on formative feedback). Therefore, there is a need to teach students how to interpret, synthesize, and construct new concepts through effective search strategies, (O’Connor & Sharkey, 2013).

Putting the Theory into Practice: The Content Curation Investigation.

When challenged to develop a personalized question addressing information fluency, my nutrition research class resurfaced. These researchers-in-training need to develop content curation skills as an essential part of conducting research. One assignment in that course reminded me of the O’Connor & Sharkley conundrum. Students are required to conduct a literature search through the university’s library on a topic related to a food or ingredient they wish to experiment on. From this literature search, students create an annotated bibliography whose goal is to gather information on what work has already been done with a particular food or ingredient, understand the key concepts and/or patterns that emerge from that body of work, and help students refine their own work by analyzing and concluding what is still left to investigate. Historically, students “graze” through this assignment, missing that critical analysis piece. Although students do receive feedback, it is summative and not formative. Keeping all of these current issues in mind, my question began to unfold:

“What simple tech tool can effectively be used to help students better annotate and organize scientific literature when conducting a literature search?”

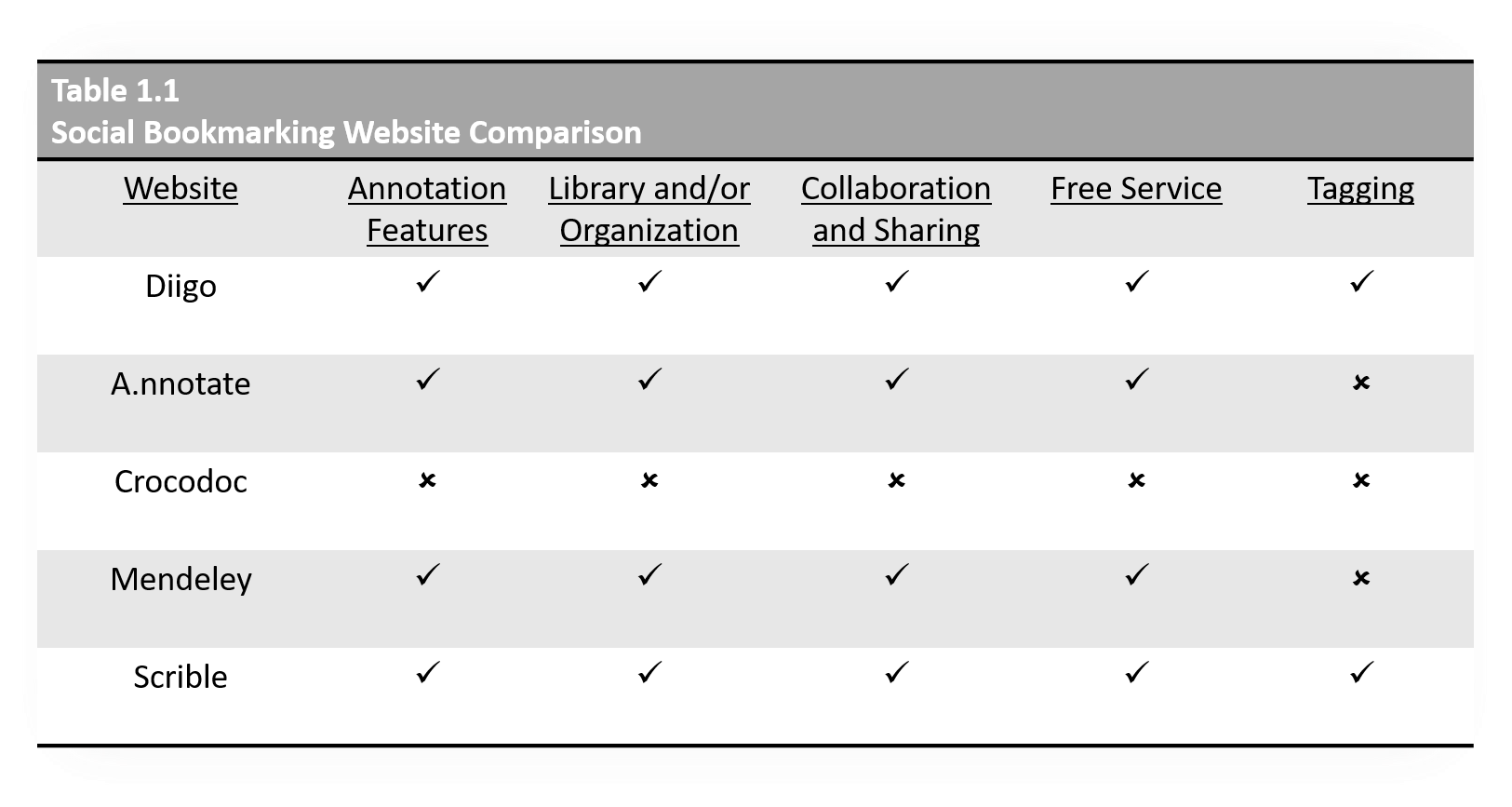

Resource Search. When investigating possible annotation tools to help students better curate and organize information from scientific literature, three main criteria came to mind. The tool must: 1) offer annotation features; 2) allow for organization of literature and/or annotations; 3) allow for collaboration and sharing. Annotation is the skill of focus for the assignment. Being able to cultivate useful information via annotation from scientific works will allow students to create connections through the practice of active reading. The goal of annotation in this sense means that students are reading to not only review what information already exists, but also analyze that existing information to infer what may be missing (i.e. literature gaps), and connect their work to the existing literature. A tool that aids in organization will also help fulfill the ISTE standard for students on knowledge curation by thinking about the literature as categories to better extract information from each resource, thereby helping to also develop their information fluency. How students classify their information will help them organize their ideas and later their final artifacts. Lastly, the ability to collaborate and share their annotation/organization is important to receive formative feedback.

My investigation began with a google search using “social bookmarking for education” and “web annotation tools for education” as keywords. Several articles from edtech sources listing the top favorites were reviewed, resulting in over thirty different types of tools and apps. To narrow this selection, I applied the three criteria above which produced five possible options. A summary of each option is provided in table 1.1 below.

Resource Comparison. From this investigation, Diigo, Mendeley, and Scrible fulfill the three criteria above without interface issues, currency issues, and are still available. Crocodoc is no longer available (R.I.P. Crocodoc), and A.nnotate’s user interface looks dated and does not offer all of the added features found on the other three websites. In fact, when searching for reviews of A.nnotate, the latest one I could find dates back to 2008. Comments in that review article suggest using Google Docs or even Microsoft Word as an alternative to A.nnotate.

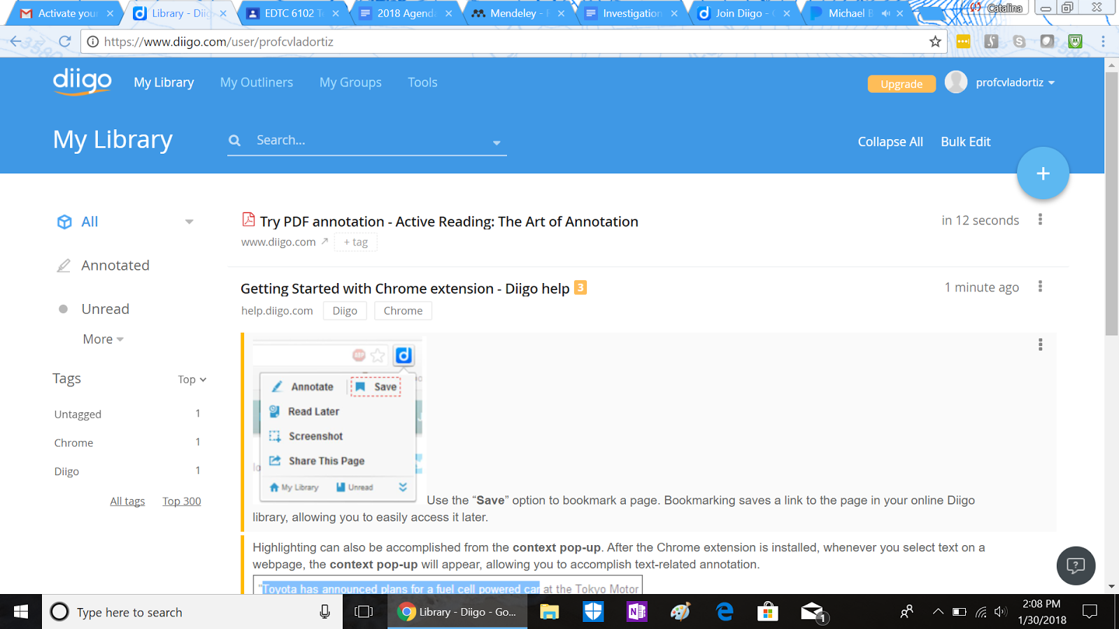

Diigo offers a library that supports multi-source uploads including pdfs, images, screenshots, and URLs into their library (see Figure 2.1 below).

The highlight feature of this app is the ability to organize and categorize resources using tags. These tags can be easily searched for quick access to a specific category or categories. The user then has the option to annotate the resource which can be shared with a group that the user creates (the assumption is that group members also have Diigo) or through a link the user shares. Other features and benefits are explored here. Diigo is a free service, or rather at sign up, the user must choose a package, the most basic is free. The free version allows up to 500 cloud bookmarks and 100 webpage and pdf highlights. The downside, the free version doesn’t not allow for collaborative annotation.

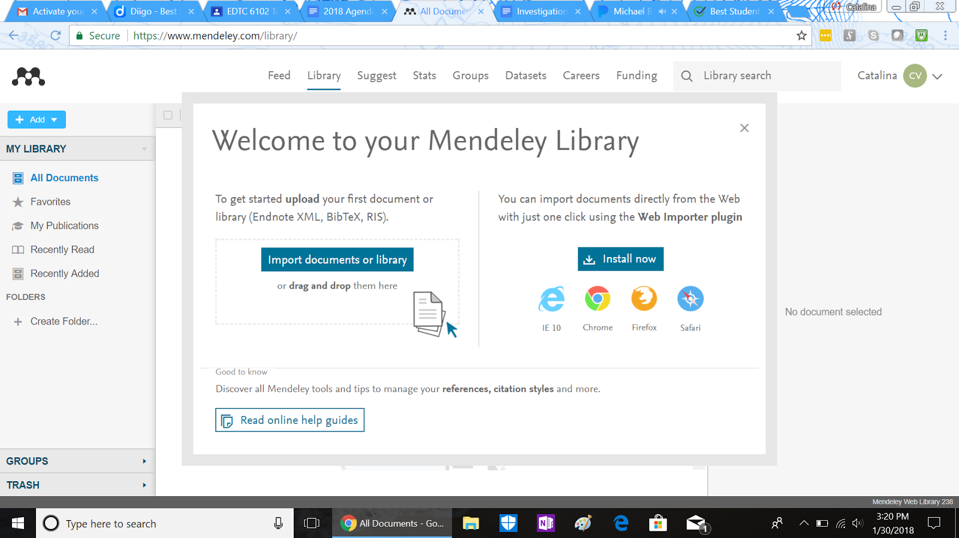

My initial impression of Mendeley is that it is very research-focused. Upon further investigation, my impression was correct as the website is a partner with Elsevier, a parent company to many peer-review journals. In the profile creation process, the user is asked to fill out a short survey on intended use and level of use (i.e. undergraduate v.s. graduate research). Like Diigo, the library allows for uploading pdfs, or articles directly from the web. The library can be organized into folders, but does not allow for tagging. See figure 2.2 below.

The annotation feature offers highlighting and sticky notes (comments). Articles can be shared via emailable link for individuals who do not have a Mendeley account or the user may elect to create a group to share documents to peers with accounts. An interesting feature of Mendeley is the desktop version of the website that saves permanent article copies to the user’s desktop to allow for offline work.

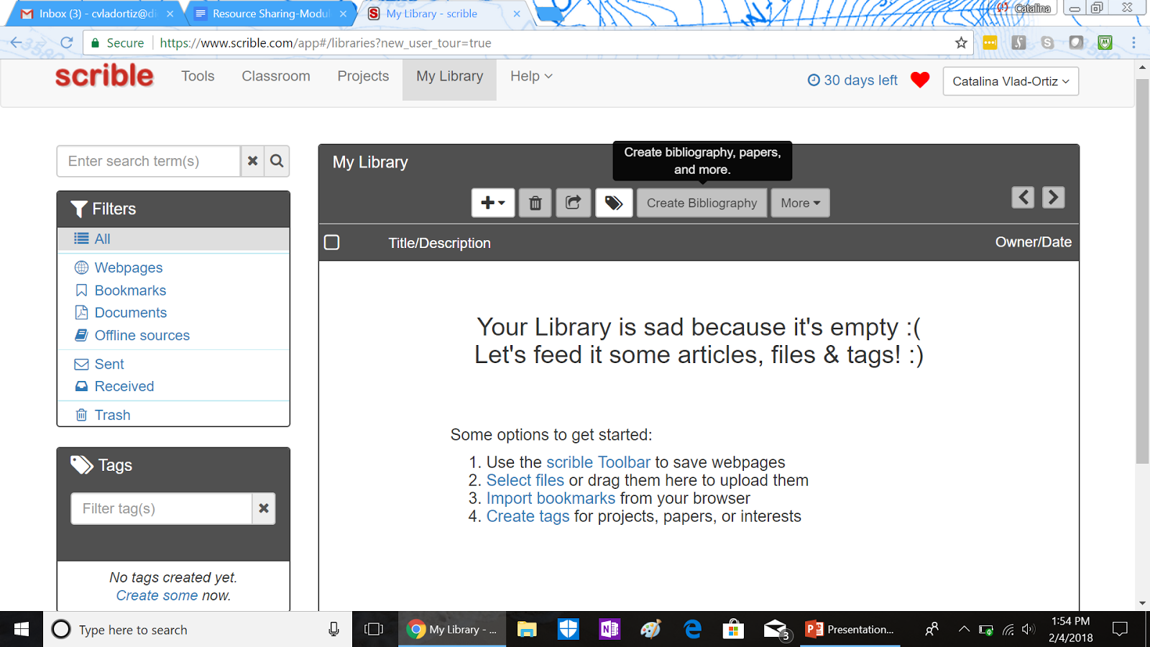

Scrible seems to be a fairly new website. While the purpose of this site is to allow for social bookmarking and web annotation just like Diigo and Mendeley, it also has a classroom feature. Educators can upload resources that all students can access. Scrible can also be incorporated into an existing Google Classroom. Students can appreciate a seamless integration with Google Docs and as an added bonus, the site will automatically create citations and bibliographies. Figure 2.3 shows the Scrible library.

The downside of this website is that while the classroom, the google doc integration, and the citation features are free for K-12 classroom use, it is not free for higher education use. Higher ed users are given a 30-day free trial and then the program converts to the basic plan which offers the exact same features as Diigo.

Conclusion. Diigo and Mendeley are easy to use, offer sharing features, and connect to social media for collaboration though neither support collaborative annotation in the free versions. In addition to the features mentioned above, Scrible does allow collaborative annotation in the basic package. Diigo seems to be optimized for websites and web articles while Mendeley is optimized for research articles, with Scrible somewhere in-between.

Since all three websites offer the same desired features, all three score highly on the Triple E rubric: 5 points on engagement in the learning, 6 points on enhancement of learning goals, and 5 points on extending the learning goals. Therefore all three would fulfill the assignment goals. In order to pick one appropriate for this assignment, I would need to consider the students. Mendeley, designed specifically for research articles, is not only a good fit for the assignment, but students could continue to use this website should they go to graduate school. Diigo is focused on web articles and could be used by students in their other classes or other aspects of their professional lives. Scrible, having more of a focus on education, may not be equally as useful outside of the classroom.

The Next Steps.

Though any of the three websites would be suitable for the annotation assignment, I do not teach this section alone. I’ve enlisted the help of the university librarian who co-teaches literature search skills for this course. She was quite enthusiastic at the thought of web-tool integration with this assignment and we will be adding another criteria addressing seamless integration with our library website and resources to make our final decision.

References.

Briggs, S. (2016, July 27). Teaching content curation and 20 resources to help you do it [Blog post]. Retrieved from: https://www.opencolleges.edu.au/informed/features/content-curation-20-resources/

Edutopia. (2016, November 1). Solving real-world problems through problem-based learning. Edutopia. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/practice/solving-real-world-issues-through-problem-based-learning

International Society for Technology in Education, (2017). The ISTE standards for students. Retrieved from: https://www.iste.org/standards/for-students.

O’Connor, L., & Sharkey, J. (2013). Establishing twenty-first-century information fluency. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 53(1), 33–39.

Shukor, N. A., Tasir, Z., Van der Meijden, H., & Harun, J. (2014). Exploring students’ knowledge construction strategies in computer-supported collaborative learning discussions using sequential analysis. Educational Technology & Society, 17(4), 216-228.