What does a “typical” college student look like? Besides the stereotypical images of a caffeine-fueled, student loan-laded, twenty-something, most people would say that the college student today is very tech savvy. While it is commonplace to see students carry around a laptop, constantly checking their cell phones, and always connected to social media, do they know how to use technology well? An article written by educational leaders Mike Ribble and Teresa Miller, introduces the concept of digital citizenship, arguing that while being tech savvy is important, being a good digital citizen should also include respect of self and others, education and connection with others, and, protecting self and others, (Ribble & Miller, 2013). In order to achieve this, they identified nine elements central to digital citizenship as summarized in Table 1.1 below.

| Table 1.1

Ribble-Miller’s Nine Elements of Digital Citizenship |

|

| Category 1:

Respect Self and Others |

· Digital Etiquette- courtesy and appropriate online actions.

· Digital Access –similar opportunities for all students. · Digital Law- basic laws, and consequences, apply online. |

| Category 2:

Educations and Connection with Others |

· Digital Communication- avoiding online miscommunication.

· Digital Literacy- technology know-how. · Digital Commerce- safe online purchases. |

| Category 3:

Protect Self and Others |

· Digital Rights and Responsibility- rules must be followed or rights are revoked.

· Digital Security- protection of personal information. · Digital Health and Welfare- balanced online- offline life. |

As Ribble & Miller demonstrate above, to use technology well requires much more than just know-how, also known as, digital literacy. Digital citizenship is a broad, complex topic that spans a variety of different issues. Questions on how students should develop digital citizenship and who should teach it, has sparked discussion in the digital education world. While responsibility should fall on many fronts, such as society, family, and peers, educational institutions also hold a responsibility to teach moral and ethical values to their students. The challenge remains, as Ribble & Miller put it: “How are educational leaders to prepare their students for a digital future when they do not yet fully understand these technologies?” (Ribble & Miller, 2013).

The nine elements of digital citizenship offer a guide to educational institutions on how to better prepare their students. As a higher education professor, my take on digital citizenship is that educational leaders need to look at technology use and requirements through various perspectives such as from faculty, administrators, and the industry. Though I have a somewhat good understanding of how faculty view technology in the classroom, I was curious to know how do administrators feel about technology and what do specific industries provide as resources for technology in their field? In preparing for this project, I identified two administrative leaders who could best provide answers to my questions. Since I teach dietetics, I also sought to understand how the dietetic profession viewed digital citizenship and/or if the profession could provide some best practices as a curriculum guide.

Digital Readiness Interview.

My objective was to first understand what students already do well in terms of digital citizenship and how well educators were prepared to teach the missing elements. This objective was completed through an interview with two of the departmental leaders at a private university.

The Procedure. The interview consisted of ten questions pertaining to the nine elements of digital citizenship, with exception to digital commerce. Digital commerce was not addressed in this interview as it was not department-specific. Questions were arranged by the digital citizenship categories (see Table 1.1). Questions from category one consisted of one question per element addressing digital access, digital law, and digital etiquette. Category two consisted of one digital communication question, and three digital literacy questions. Questions addressing category three consisted of one question per element regarding health and welfare, and digital security. Five additional questions were asked addressing digital citizenship in dietetics education.

The interview questions along with detailed instructions were emailed out to the two department leaders about two days prior to their scheduled interview to allow time for reflection. During the scheduled interview, the two leaders were asked to respond to the questions through their observations between faculty and students. The response data was collected and compiled for interpretation, coding any similarities and themes among the responses.

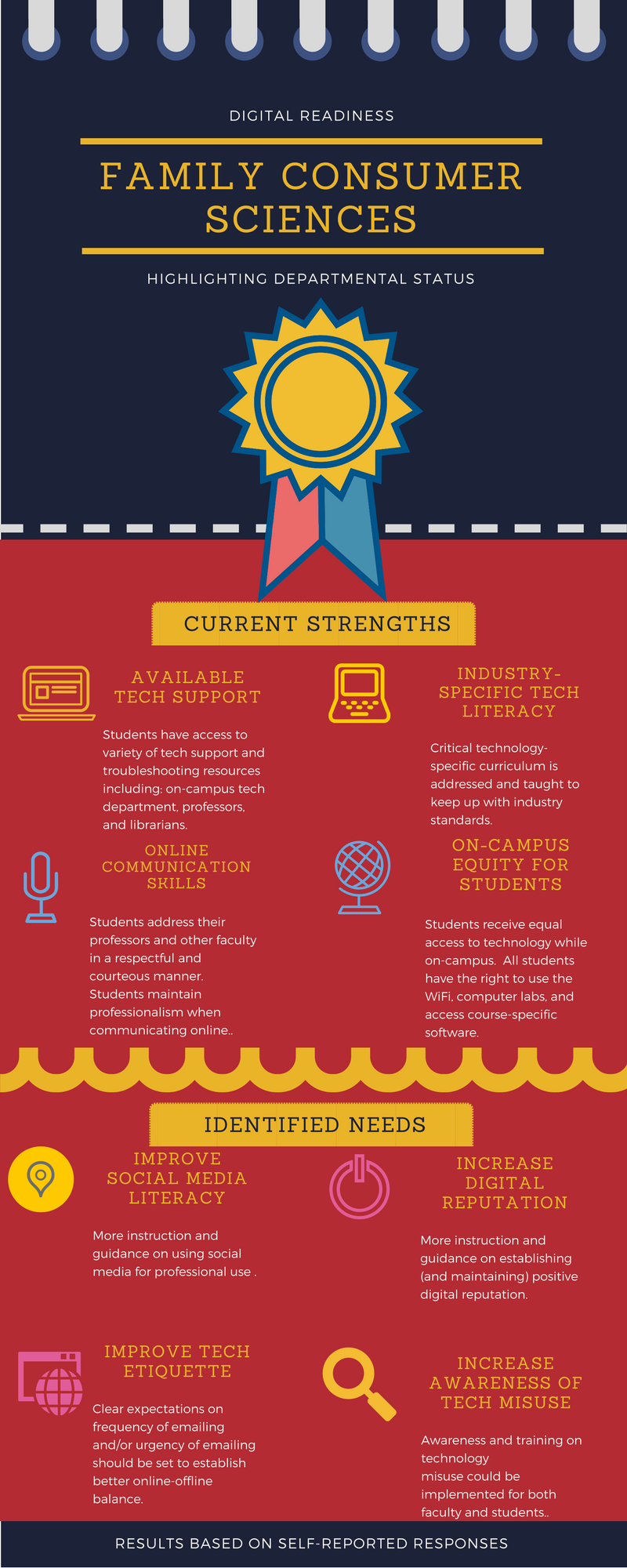

The Interview Findings. The findings of the digital readiness interview positively showed that students demonstrated competency in, or the department was able to provide ample resources for the following digital citizenship elements: digital etiquette, digital access, digital law, digital communication, and digital literacy. Though these were positive results, small improvements were identified in the areas of digital communication, etiquette, and literacy. For example, a strength identified in digital literacy was providing instruction in industry-specific software, but minor additions could be added to enrich professional social media skills to help better establish a positive online presence. Students also demonstrated good digital etiquette by communicating with their professors in a professional manner but tended to email their professors with questions that could be easily answered through resources readily available through their class syllabus or through the department website. The other elements of digital citizenship were identified as either addressed by the department but to a limited extent, or not addressed. These elements included: digital rights and responsibilities, digital security, and digital health and welfare. Though these elements are addressed by the university through available student resources, improvements on the departmental level can help reinforce these elements. Of these elements, digital security, was identified as an immediate need and steps were taken to help develop awareness and professional development after the interview. The interview findings identified as strengths and areas of improvement are shown in the infographic below.

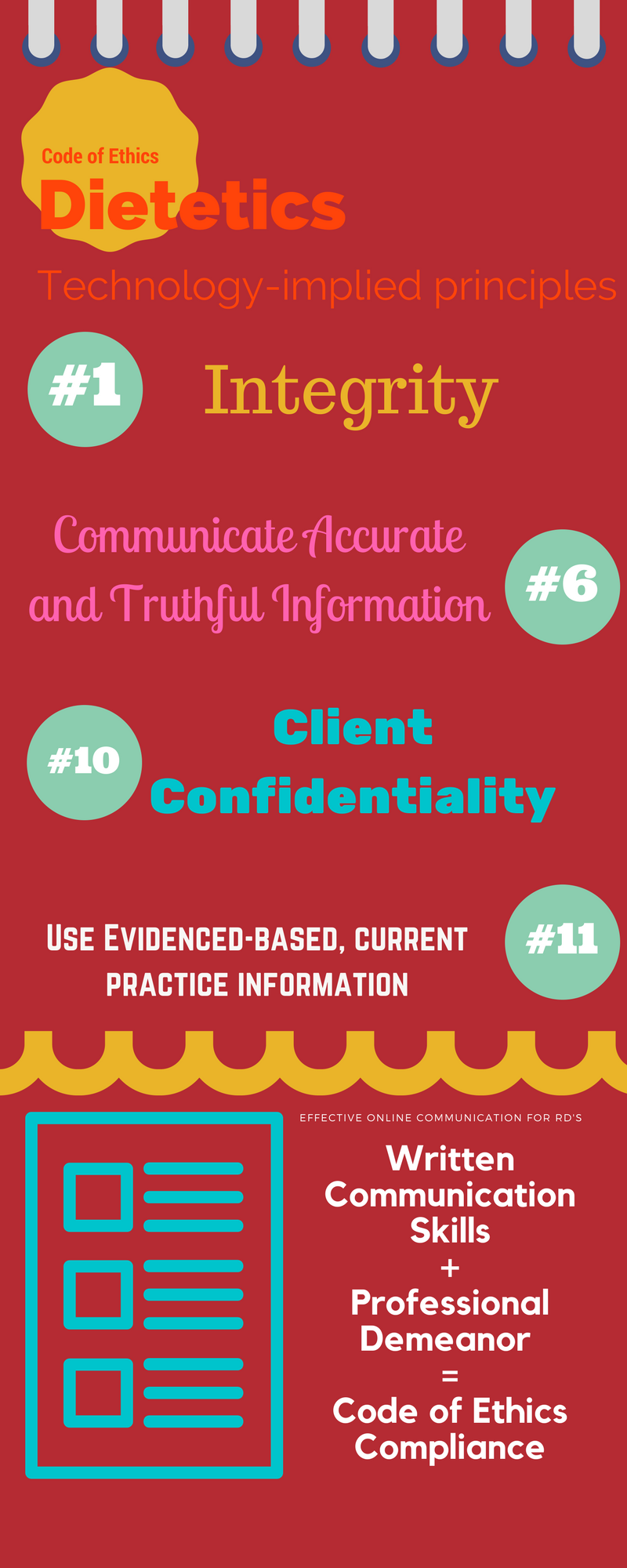

For the dietetics specific questions, it was determined that the current code of ethics could be used to address digital citizenship concerns. Since the practice of dietetics relies heavily on this code, adhering to the code would help guide good digital citizenship. The specific principles that align with digital citizenship are summarized in the infographic below.

Reflection and Conclusions.

The main issue regarding digital readiness, in my opinion, is that educators, including professors, feel like digital immigrants, meaning that they did not grow up with technology and do not feel comfortable with technology. They may be slow adopters as new technology develops, putting a critical eye into the utility and purpose of each new technology. Professors may feel a little behind as their students, demonstrating characteristics of digital natives, understand and adopt technology quickly as they have been using technology their whole lives, (Floridi, 2010). Despite whether someone self-identifies as a digital native or immigrant, it still does not necessarily equate to knowledge of good technology use. Therefore, the role of the educator in teaching digital citizenship, is to prepare college students for the professional challenges in technology that lie after leaving the safe and secure environment of the university. This is why teaching digital citizenship is very important. We need to teach students these skills while allowing them to practice in an environment that is easy to recover from an error.

The results from the department interview showed a commitment to building good digital citizens. The areas identified for improvement didn’t seem to come as a surprise but rather an acknowledgement that more guidance and support was needed in order to successfully enrich the department programs with the nine elements of digital citizenship. Given the positive attitude and the open-mindness of the department, all of the elements can be easily incorporated following the JISC recommendations including adapting digital citizenship into existing learning outcomes, (JISC, 2015). After the interviews, each department leader and I spent a little bit of time brainstorming ideas and were able to successfully identify several minor adjustments to current curriculum, including assignments and course design elements to better improve social media literacy for professional use, digital communication, digital health and welfare, and digital security. As it turns out, the timing was also critical, given that the department was in the midst of evaluating current curriculum, the brainstorm helped to look at what being taught in a new light. In order for the department to fulfill all of its digital citizenship needs, it will need to seek some outside help and set-aside time for professional development. This is an effort that will require time and significant effort but no more than what is already needed in order to ensure that the students are able to be competitive in their respective industries by graduation.

In terms of digital readiness, what professors need to realize is that the critical thinking and evaluation skills that makes them “slow-adapters” to technology is not a bad thing. As in the case of the department, the curriculum-wheel does not need to be reinvented, but instead what is needed is a good revamp of the traditional elements of curriculum with a technology-focused twist. As explored in the post-interview discussions, not all new tech is good tech. Not every technology will provide optimal functionality and purpose as the current model/version. Educational institutions have a lot to offer to students. The key is to forget about digital natives and digital immigrants and all work towards becoming good digital citizens.

References

Floridi, L. (2010). “The Information Revolution,” Information—A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3-18.

JISC. (2015). Developing students’ digital literacy. Retrieved from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developing-students-digital-literacy.

Ribble, M. & Miller, T.N. (2013). “Educational Leadership in an Online World: Connecting Students to Technology Responsibly, Safely, and Ethically,” Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 17:1, 137-45.